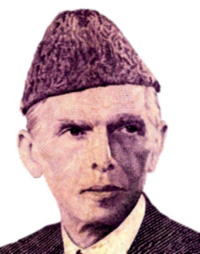

Jinnah, Mohammed Ali

Jinnah, Mohammed Ali (1876-1948) lawyer, politician and founding father of Pakistan. He was born on 25 December 1876 in Karachi where his parents migrated from their native land Kathiawar, on the west coast of India. Jinnah had his early education in a school in Karachi, Gokul Das Tej Primary School in Bombay, Sind Madrasa High School in Karachi and then entered the Christian Missionary Society High School in Karachi.

Having passed his matriculation from the Missionary Society High School, Jinnah sailed for London in 1892 to study law at Lincoln’s Inn. He returned to Karachi in 1896. He moved to Bombay in 1897, but the first three years of his legal career were of great hardship. His fortunes changed at the turn of the century. Once he was established, Jinnah probably earned more than any other lawyer in Bombay. Jinnah’s first active move toward politics took place during the 1906 session of the indian national congress in Calcutta in the wake of the Hindu community’s adverse reaction to the proposed partition of bengal in 1905. Dadabhai Naoroji’s slogan, Swaraj, was now writ on the new banner of Congress, behind which Jinnah marched.

Jinnah's ascent to political influence began with an important piece of legislation passed by British Parliament in 1909, the Indian Councils Act, expanding the Viceroy's Executive Council into the Imperial Legislative Council by the addition of 35 nominated members and 25 elected members with special representation for Muslims and landowners. Jinnah became one of the elected members of the Council from Bombay. His association with the muslim league began in 1911. At its next session in December 1912, which Jinnah attended, the League proposed to amend its Constitution so that it would ally with Congress in a common demand for 'Swaraj'. On request from Maulana Mohammad Ali and Syed Wazir Hassan, Jinnah joined Muslim League in 1913.

In the autumn of 1916 he was elected once again to the Imperial Legislative Council. In December 1916 he succeeded in prevailing upon both Congress and Muslim League to hold their annual sessions at Lucknow. Jinnah presided over the League session. The sessions warmly assented to the 'irreducible minimum' of reforms worked out by their joint committee and passed it to the Government of India. The main domestic problem of separate electorates was overcome with Congress agreeing to Jinnah's plea to allow weightage of seats in the legislative councils of certain provinces where the Muslims were in the minority. This became known as the historic Lucknow Pact and it made Jinnah a leader of the Indian Muslims.

After the Rowlatt Act was passed in March 1919 to give the Government of India summary powers to curb seditious activities, Jinnah in protest resigned from the Imperial Legislative Council, and Gandhi launched a movement of non-violent Civil Disobedience. In early April Gandhi's followers resorted to rioting in Amritsar killing three European bank managers. This led to the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh on 13 April 1919. Then Gandhi called off his civil disobedience movement. Jinnah's disillusionment became complete during the Congress session at Nagpur in December 1920, and after this he parted with Congress. His link with the Muslim League was also getting bitter, because aristocratic Muslim leadership was not inclined to abandon their traditional loyalty to the raj and considered the British as their patrons. The promises made by Congress in Lucknow Pact in 1916 were never honoured, and the rift between the two communities continued to widen.

For Jinnah the decade of the twenties was nothing but a series of political frustrations, especially centering round British bungling with reforms, refusal of Congress to recognize the need to provide representational guarantee to the Muslims, Gandhi's populist methods to deal with the fate of the Indians and the miserable dilemma of the Muslims as to their position and strength. After attending the first fruitless Round Table Conference in London in 1930 Jinnah found himself overshadowed in the second conference by the Aga Khan as leader of the Muslim delegation, and by Gandhi. He was not included in third conference and was not thought to represent any considerable school of opinion. In 1931 he decided to settle in London and abandon Indian politics for ever. Jinnah started practicing at the Privy Council Bar.

The Government of India Act of 1935 contained the so-called Communal Award that laid down the pattern of representation to the various legislatures to satisfy the minorities, especially Muslims and the Scheduled Castes. The Act provided electoral politics holding out great prospects for the non-aristocratic nationalist politicians. Under the changed circumstances, Jinnah was motivated by some Muslim middle class leaders to come back to India and take the leadership of the Muslims. The elections under the Act in 1937 shockingly proved that the 100 million Indian Muslims were hardly a coherent community; they were disparate, unknown to each other and shared nothing in common but religion. In the North-West Frontier Province, where the Muslims constituted the 90% of the population, not a single Muslim League candidate returned to the legislature.

In the Muslim majority Punjab, the Muslims were organised under older parties and showed no interest in Jinnah's revived Muslim League. The Muslims in Sind had openly disowned the League and allied themselves with Congress, rejecting any suggestion of partition. It was only in Bengal that the Muslim League scored an electoral victory by securing the second highest majority and forming a coalition government with Krishak Praja Party of AK Fazlul Huq. In 1938, Jinnah himself founded in Delhi an English newspaper Dawn to fight the propaganda of the Hindus. By 1940 Jinnah started speaking of 'two nations' and on March 23 of that year he presided over the All India Muslim League session in Lahore that adopted the Pakistan Resolution moved by the chief minister of Bengal, AK Fazlul Huq.

Following the failure of the Cripps Mission, Gandhi launched his quit india movement. Gandhi, Nehru and other members of the Congress high command were taken into custody on charges of sedition. On 26 July 1943 Jinnah narrowly escaped an attempt on his life by a Khaksar volunteer.

Jinnah accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan which the Congress rejected. In retaliation Jinnah also withdrew his concessions. On 28 July 1946 the Muslim League at its council meeting in Bombay withdrew its acceptance of the Cabinet Mission proposals, and declared Direct Action to force the cause of Pakistan, and protest Viceroy Lord Wavell's invitation to Congress (8 August 1946) to form an interim government at the centre. The Direct Action Day on August 16 set off the great Calcutta killing annihilating no less than 4000 Muslims and Hindus. In October and November about 8000 Muslims were killed in Bihar. Similar killing of Muslims took place in the United Provinces.

Early in October Jinnah agreed, after further discussions with the viceroy, to nominate to the interim government five Muslim League ministers headed by Liaquat Ali Khan. The last viceroy Lord Mountbatten arrived in Delhi on 22 March 1947 to preside over the partition of India. On 7 August 1947 Jinnah flew from Delhi to Karachi to be sworn in as the first Governor General of Pakistan on 14 August. It was due almost entirely to his leadership and his people's loyalty to him that the truncated infant state of Pakistan was able to tide over the myriad initial problems and stand on its own feet. Mohammed Ali Jinnah died on 11 September 1948 in Karachi. [Enamul Haq]