Arabic

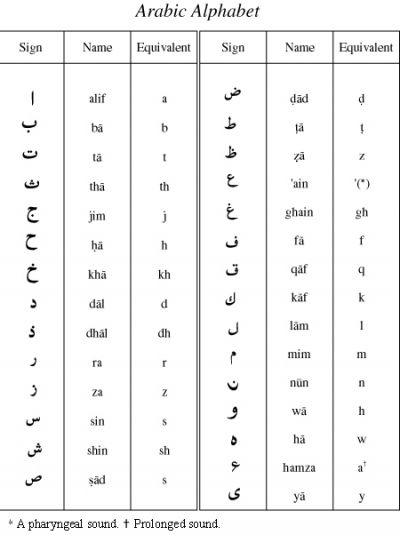

Arabic a Semitic language spoken by people in the Arabian peninsula and North Africa; the language of the Holy quran and Muslim prayers. It has its own distinctive script, which has spread with islam and is used for writing several other languages of the Muslim world, including urdu. Arabic does not have vowels; all expressions in it are effected with the help of consonants. There are signs to indicate vowel sounds, but they do not generally appear in writing. This makes reading the script a little complicated.

The roots of most Arabic words are composed of three letters. Verbs have two tenses: past and present. The present tense is used to indicate the future as well. Verbs indicate tense, person, gender and number. For instance, kataba (he wrote) signifies past tense, first person, masculine gender and singular number. There is no neuter gender in Arabic; a word is either masculine or feminine. For instance, shams (sun) is feminine, qamar (moon) is masculine. In structuring a sentence, the word for 'no' is placed before the verb.

Unlike Arabic, Bangla belongs to the family of Indo-European languages. This is why there is little similarity between Arabic and Bangla in vocabulary and grammar. Bangladesh is also quite far from the Arab hemisphere. Nevertheless, the people of this country became familiar with Arabic initially through trade and then through the advent of Islam. Arab traders used to come to the coastal ports of chittagong or sandwip in boats laden with merchandise and from there they would proceed to the ports of Myanmar (Burma), Malaya and up to China. After the advent of Islam, Sufi devotees accompanied the traders. In due course, some people were converted and started learning Arabic. The mosques and khanqahs, established by Muslim missionaries for religious purposes, provided facilities for teaching the Quran in Arabic. This is how the learning of Arabic began in Bengal.

Arabic vocabulary began to enter Bangla from the 7th-8th centuries through Arab traders and Muslim missionaries. This led to Arabic vocabulary, such as Islam, iman, zakat, Hajj, imam, murtad, wazu, ghusal, fard, wajib, sunnat, halal, and haram entering Bangla with some changes in pronunciation. Other Arabic words have undergone considerable changes in pronunciation and spelling, for example akuf (Ar. waquf=to know), ajura (Ar. ajar=wage), jera (Ar. jaraha=arguments), bada (Ar. bayda=egg), and mane (ma'na=meaning, significance).

The rural dialects of Bangladesh, especially those of Chittagong and noakhali, contain plenty of Arabic words. Nearly a half of the words of the Chittagonian dialect are Arabic or of Arabic origin. The use of the negative before verbs in this dialect reflects the influence of Arabic.

A large-scale borrowing of Arabic words occurred during the Muslim rule in the subcontinent. persian was then the state language and its influence was overwhelming, enabling many Arabic words, common in Persian, to enter Bangla. For instance, the Persian ziyafat, rather than the Arabic diyafat (hospitality, entertaining), is used in Bangla. This link between the two languages never snapped. In fact, the spread of Islam in this country strengthened the link further.

Some of the Sufis who came to this country before the Muslim conquest of Bengal in the 13th century were Shaikh Ahmad (or Abbas) Ibn Hamza Nishapuri (9th century), baba adam shahid (11th century), shah' sultan rumi (11th century), Shah Sultan Mahisawar and makhdum shah daula shahid. It is believed that they established mosques, khanqahs and maktabs at different places as part of their mission to propagate Islam. There is proof that Sufi devotees set up educational institutions. For instance, Maulana Taqiuddin Al-Arabi (13th century) was the founder of the madrasah at Mahisun in rajshahi, perhaps the first institution of Islamic learning in this country. It used to teach Arabic and Islamic subjects Shaikh sharfuddin abu tawamah established a madrasa at sonargaon in dhaka district, perhaps at the beginning of 1280. Its standard was quite high. The well-known Sufi Shaikh sharfuddin yahya mAneri studied here for 22 years. Its curriculum also included scientific studies.

The reputed Islamic theologian and educationist, Maulana Abdul Bari, came to Buhar in Burdwan district at the request of Munshi Sadruddin, the zamindar of Buhar. A madrasa was established in Buhar in 1764. All its expenses were borne by the zamindar. Years later when the madrasa closed down, its huge and precious library was, at the direction of the British Indian government, added to Calcutta's Imperial Library (now Indian National Library) as the 'Buhar Wing'.

As Muslim rule spread, many more madrasas were established in different parts of Bengal. On an average, there was one maktab or madrasa for every 400 persons. According to an account by the Indologist Max Mueller, there were as many as 80,000 madrasas in East Bengal in the early 18th century. These madrasas used to teach Arabic so that students could say their prayers and recite the holy Quran and wazifa (daily prayer book) correctly. Arabic writing was only taught in the higher classes.

The madrasas in Bengal followed the curriculum and teaching techniques of the Muslim world. The curriculum was divided into two parts: religious and intellectual. The religious part included 'ilmul qira'a (reading Arabic with the correct pronunciation), phonetics, tafsir of Quran (commentary), hadith, al-fiqh (jurisprudence), al-kalam (theology), Arabic language and literature, Arabic grammar and rhetoric, and mirath (science of inheritance). The second included mantiq (logic), hikmat (ethics) and falsafa (philosophy), astrology and palmistry, mathematics, geometry, civics, medicine and music (hamd, na 't, ghazal etc).

Maktab and madrasa students took about seven to ten years to complete their studies. Some madrasas were earmarked for higher studies. An educated person was required to gather specialised knowledge in the Quran and hadith as well as fiqh. An adequate knowledge of Arabic was considered essential as it was the language of the Quran and hadith as well as of the original books of fiqh.

A considerable number of Arabic books were written in East Bengal during the years of Muslim rule. Hawdul Hayat by Kazi Ruknuddin Samarkandi (12th century) was an Arabic translation of Amrtakunda, a sanskrit text on yoga. Allama Abu Tawwamah wrote Maqamat on Sufism. During the governorship of Nasiruddin Bughra Khan in Bengal (1283-1290), a scholar named Kamil Karim wrote Majmu'i-khani fi 'Ayni'l Ma'ani, on jurisprudence. Shaikh Kutbul Alam published a collection of hadith entitled Anisul Ghuraba. Some works in Arabic were, however, just transcriptions of Arabic texts. For example, Muhaddis Muhammad Ibn Jajdan copied the three volumes of Sahih Bukhari in his own hand writing.

Arabic education suffered a setback after the Mughal emperor in Delhi granted the diwani rights in Bengal to the English in 1765. Soon all Islamic education institutions, apart from some mosque-based maktabs, were shut down. This, however, created difficulties for the English, specially in administering justice, as all administrative activities till then had been conducted according to Muslim law. In response to representations by several Muslim leaders, WARREN hastings established Calcutta Aliyah Madrasa in 1780. This restarted madrasa education in Bengal. The curriculum of the madrasa was designed by Molla Nizamuddin Sihalvi (?-1748). It included hadith, tafsir, fiqh, Arabic grammar, rhetoric, logic, Greek philosophy, and kalam (aqidah).

Arabic literature was not part of the curriculum, but the Quran and hadith were studied as literature. In 1871 the study of tafsir and hadith was discontinued, but Arabic literature was made part of the curriculum. Texts studied in the higher classes included Maqamat Hariri in prose and Diwan Mutanabbi and As-sab 'ul-Mu 'allaqat in verse.

Hughli Madrasa was established in 1871, and in 1873 three more madrasas were established at Dhaka, Chittagong and Rajshahi. These institutions, which were run by the government, followed the curriculum of calcutta madrasa. In 1837 Persian lost its status as the state language, and in 1857 the university of calcutta was established. While Muslims reacted adversely to the displacement of Persian, they also realised the imperative need for learning English. In 1826 Calcutta Madrasa started teaching English. The introduction of Arabic language and literature in the general schools and colleges as an optional subject began in 1872-73. At the beginning there were few students, but this changed slowly and almost all Muslim students took Arabic as an optional subject. In due course honours and masters courses in Arabic were introduced.

Another stream of madrasa education - the New Scheme Madrasa - was introduced in 1915 to modernise education without adversely affecting Islamic learning. English was made a compulsory subject along with Arabic. Higher secondary classes were added later to enable students to enter universities. Under this scheme, to which Shamsul Ulema Abu Nasar Muhammad Waheed had contributed significantly, government intermediate colleges were established in Hughli, Dhaka and Chittagong.

The Calcutta Aliyah Madrasa was moved to Dhaka after the creation of Pakistan in 1947. The Pakistan government, however, did not show much interest in madrasa education, and the New Scheme was allowed to die in 1965-66, barely 50 years after its introduction. Although Arabic departments continued to exist in the universities, many colleges discontinued courses on Arabic.

Yet another stream of madrasa education, known as qaomi madrasa, has been current in Bangladesh for a long time. Some well-known madrasas of this stream are those at Hathazari and Patiya in Chittagong, at Lalbagh and Jatrabari in Dhaka, at Baliya in mymensingh and Jamiya Imdadiya at kishoreganj. The number of such madrasas is on the increase. Arabic, with an emphasis on grammar, is compulsory in their curriculum. The classes are also named after grammar books, such as Mizan, Nahwmir, Hidayatun Nahw.

When the university of dhaka was founded in 1921, Arabic and Islamic Studies formed one of its twelve departments. Students passing IA (Group C) from the Islamic intermediate colleges could get admission into this department but not those graduating from Aliyah Madrasa.

The 19th century saw significant publications in Arabic. Maulana karamat ali jaunpuri, a missionary and reformer, wrote four books in Arabic. Da'wat Masnuna, which is in Arabic and Urdu, explains how God's blessings may be sought through Quranic verses. Two of his books, Mulakhkhas and Barahin Qat'iya fi Mawludi Khayri'l-Bariya, are on the subject of milad. His fourth book, Nasimul-Harmayan, discusses Islamic thought and the controversies that have arisen therefrom. Maulana ubaidullah al ubaidi suhrawardy was a distinguished educationist and superintendent of Dhaka Muhsinia Madrasa. He wrote five books in Arabic as well as poems. Khan Bahadur Abdul Karim Khaki (?- c 1891) wrote Jami'ur Rumuz, a commentary on a book of fiqh, in Arabic His Tafsiru fathil-kalam is a book of annotations in Arabic.

Even non-Muslims in Bengal made considerable contributions to Arabic language and literature. In 1803, Raja rammohun roy, (c 1772-1833) founder of brahma samaj, wrote Tuhfat ul Muwahhidin, on the oneness of God, in Persian. The book has a long preface in Arabic. The first work of girish chandra sen (1835-1910), after he learnt Arabic, was to translate the holy Quran into Bangla; he also translated parts of Mishkat Sharif into Bangla.

Arabic teachers became interested in writing Arabic textbooks after some changes were made in the madrasa curriculum, and the teaching of Arabic was introduced in schools and colleges. Significant contributions were made in this field by Maulana Muhammad Musa (?- 1964), Mufti Syed Muhammad Aminul Ihsan (?- 1974), Maulana Alauddin al-Azhari and shamsul'ulema abu nasar waheed (1872-1953), They mainly compiled texts from Arabic books although they also did some original writing, for instance, Maulana Musa in Subhatu'l- Adab and Kitabu'l Amalih. Mufti Aminul Ihsan wrote some valuable texts on tafsir, hadith and fiqh, such as Qawa'idul-Fiqh and Fiqhus-sunan wal Athar, which discusses hadith and fiqh from the viewpoint of the Hanafi school of Islamic thought. Maulana al-Azhari also wrote a textbook in Arabic: Al-Adabu'l-'Asri. Shamsul 'Ulema Waheed wrote five books in Arabic, based on the curriculum of the New Scheme madrasas. Maulana Abdul Awwal Jaunpuri published some 40 books in Arabic, on literature, history and religion. Maulana Abdullah al-Qafi (d 1960) published twelve books in Arabic on a variety of subjects.

Apart from writing commentaries on hadith and fiqh or textbboks to be used in the madrasas, some Bangali writers also composed fine poems in Arabic, especially qasida (poems in praise of the Prophet). Among them are Syed Abdur Rashid Shahjadpuri (?- c 1915), Mufti Azizul Huq (?- 1960), Maulana abdur rahman kashgarhi (1912-1971), Hafez Muhammad Kubbad (?- 1975) and Shamsul Ulama Bilayet Husain (?- 1984). Bilayet Husain's poem, Al-Bitaqah, was for some time part of the MA syllabus in the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies of the University of Dhaka. Maulana Kashgarhi's Az-zaharat has some fine poems on a variety of subjects.

Some momentum was given to the cultivation of Arabic and Arabic literature after liberation in 1971. The islamic foundation bangladesh was established in Dhaka in 1975. Several Arabic books on Islam have been published by the Islamic Foundation, among them, AKM Ayub Ali's 'Aqidatul Islam Wal Imam Al-maturidi and Muhammad Mustafizur Rahman's Tawilatu Ahlis Sunnah.

The islami university was established in 1985. It has a faculty of Islamic Studies under which there are a department of Arabic and three departments of Islamic Studies. The last three departments have Arabic as their medium of instruction. The general universities in Bangladesh also have departments for the study of Arabic. The Arabic departments have a large intake of undergraduate students. Most students go on to graduate studies, with some students obtaining MPhil and PhD degrees every year. Some write their theses in Arabic. The first Muslim student to receive a PhD degree from the University of Dhaka, Rajab Ali Mirza, was a student of the Arabic department. These days many Bangladeshi students with degrees in Arabic go to universities in the Middle East for higher studies.

A number of Arabic journals were published after independence, among them, Ath-thaqafah, edited by Alauddin al-Azhari, and Majallatu'l-Muwassati'l-Islamiyyah, published by the Islamic Foundation (both have since ceased publication). Since 1993, the Arabic department of Dhaka University has been publishing a journal in Arabic, Al-Majallatu'l 'Arabiyyah. Among other journals are Ikra (published by Darul Arabiah in Dhaka), the monthly Al-Kalam, edited by Harun Islam Abadi, Al-Islah published by Al-Markazul Islami, Dhaka, and the monthly Al-Huda published from Dhaka. [ATM Muslehuddin]

Bibliography Abdus Sattar, Tarikhe Madrasaye Aliyah, 1959; SMG Hilali, Perso-Arabic Elements in Bengali, Dhaka, 1967; Abdul Karim, Banglar Itihas (Sultani Amal), Bangla Academy, Dhaka, 1977.