Pata Painting

Pata Painting (patachitra) a traditional art form characterised by religious and social motifs and imageries. Pata is a Bangla word evolved from the Sanskrit patta meaning cloth. An art work drawn on a piece of silk or cotton or any other fabric portraying traditional motifs of religion and society is called pat art. As an art form pat is very ancient. Though much weakened under the impact of modernity, this form of art is still practised by uninitiated rural artists and still in demand in the folk society. As a folk art it makes an important element of Bengal cultural heritage.

Pata art is of two kinds - art on broad sheet of folded cloth and eye-art on short piece of fabric. The fabric in fact makes the base for pat art. Clay, cow-dung and some sticky elements are skillfully sprouted on the fabric. When dried, the fabric becomes tough but mellow enough for sustaining the stroke of the artist's brushes. Pata artists draw on it religious motifs, such as gods and goddesses, Puranic stories, slokas, etc. The pictures illustrate the religious and spiritual symbols the folk society likes. Kailas, Brndaban, Oudh and other holy places of the Hindus usually appeared in the pata art. This art form flourished particularly during the Buddhist period in Bengal. The pata art carried the life sketch of the Buddha and of his sayings and anecdotes. The Buddhist monks traded on pata arts very extensively. From the eighth century onward, the pata tradition was taken over by the Hindus. Yadu, Yama, chandi, ten incarnates, deeds of Rama, loves of Krishna, tale of Gazi etc became the themes of Hindu pata art.

A narrative type of folk painting is still being practised by a particular chitrakar (Painter) community in West Bengal (India) and in Bangladesh. Its origin is unknown. The origin of the chitrakar community too remains a matter of speculation. Mediaeval Hindu society, obsessed with the notions of propriety, had developed a caste system based on professional hierarchies. brihaddharma purana relates about the nine sons born out of Vishvakarma's union with a woman of lower caste. Supposedly, the pata painter was the youngest of the nine.

These nine sons or Nabasayakas were destined to do physical labour. While the eight of the Nabasayakas improved their lots socially through professional and other means, the chitrakar failed to do so and alone carried the stigma of his birth. The community eventually embraced Islam en masse for their social upliftment. However, since the community practised idolatry, it was not accepted into the mainstream of Muslim society. Hence the community maintains an ambiguous identity. Within the community the members are known by their Muslim names; the Hindu clientele knows them by their Hindu names. The common surname chitrakar signifies their profession.

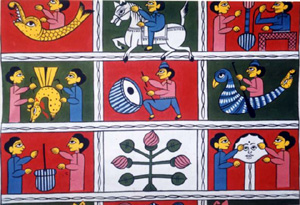

Pata painting is not a saleable commodity, it is a means for sustaining a hereditary profession. The style too is handed down the generations. Patua, Patidar, Pata are the names by which a chitrakar is commonly known. He is a poet-painter-singer. He rhymes a narration around an episode of some Hindu mythology that imparts a moral lesson. He paints the sequences in a series of rectangular frames in vertical format as a scroll painting. To the clientele, he unfurls the scroll frame by frame as his narration set to tune proceeds. The moral lesson makes listeners aware of the vices and virtues of life.

The schematic style does not reveal any urge for artistic innovation. The training in the handed down style includes memorisation of set patterns, lines, colours, and the poses and postures of the trends left by the forefathers. Despite some limitations, the style shows unique formal simplification and superb colour orchestration. It features all the traditional qualities of Bengal folk art. This art is addressed to a culturally homogeneous public that is accustomed to the images. It is painted on paper or on starched cloth. The figures painted in frontal view reveal three quarters of the face.

The palms are clinched in to a fist. The drawings, both hieratic and diagrammatic, lack spatial depth. Colours are vivid and flat. Body gestures denote action, but the faces lack expression. Black lines around the contours show linear divisions within the form. The palette contains pure pigments and vegetable dyes. For black, lamp-soot is used.

In addition to scroll painting or Jadano pata, which contains more than twenty frames, there is ade-latai or the oblong scroll, containing six to eight frames. Jam pata or Jadu pata and the Chakkhudan pata, dealing with eschatology, are painted for a family that has recently suffered bereavement. The chitrakar draws on folk literature to depict Hindu themes. The human and the divine look alike, and share the same features but for the crowns and some iconographic signs.

The narrations too obliterate the marginal boundaries between the real and the unreal. The popular mytho-religious themes are Mahisasurmardini, Kamale-Kamini, Behula-Lakhindar, Manasa-Chandsadagor, Radha-Krsna, Chaitanyaleela.

Stories of Marang-Buru, Mara-Haja, and Pichlu Buri are painted for the Santal community. For a mixed clientele, Pir pata showing miracles performed by Pirs are painted. Rashi pata showing zodiac signs is also popular. Like Yama, Jadu and Chakkhudan patas, Rashi pata serves magico-religious purposes.

From the 12th/13th century to the end of the nineteenth century patuas or pata artists were very active in this art. The main centres of pata art were Dhaka, Noakhali, Mymensingh and Rajshahi in Bangladesh, and Birbhum, Bankura, Nadia, Murshidabad, Hughli and Midnapur in West Bengal. At fairs, hats and bazars, the vendors would display the pata arts and sing pata songs to attract buyers. Such a display and the songs entertained the common people many of whom bought pata arts to hang at home in religious reverence. While pata art on a long sheet of cloth was the general feature, another genre of pata art was the eye-pata.

An imaginary picture of a dead man or woman is drawn without eyes. The vendor would seek money from the kith and kin of the dead man on the plea that the dead person would not find his way to heaven unless eyes were added to the picture. The eye pata naturally had a market on sentimental and superstitious ground.

Once Gazir pata was very popular in Bangladesh. Shudir Acharya of Munshiganj was a noted patua for Gazir pata. He drew Gazir pata on a gamchha (a thin cotton towel). On a piece of gamcha measuring 1' x 8' he made a ground with brick powder and glue made of tamarind seed. Then he drew a tiger with Gazir as its rider in red, black, yellow and green. On the body of the tiger was painted 24 pigeon-holes in which were housed Makar army, stick of Gazir, khandua tiger with stripes), yamadut (messenger of death) and so on. This genre was also called yamadut pat, because of the preeminence of yamadut. Gunai Bedey of Narshingdi sings patua songs and display Gazir pata for sale. asutosh museum of indian art and Gurusaday Dutt museums in Calcutta hold Gazir patas.

The folk tradition of patachitra is now held in low esteem owing to rapid urbanisation. Most of the members of the community have shifted to other and more lucrative professions. Those who have given up their hereditary profession have also discarded their Hindu identity. [Sovon Som and Tofael Ahmad]