Adina Mosque

Adina Mosque at Hazrat Pandua or Firuzabad, in Malda district of West Bengal, was the largest mosque in medieval times not only in Bengal but also in the whole of the subcontinent. It was, according to an inscription at its back wall, built in 1373 AD by sikandar shah, son of iliyas shah. For a sultan like Sikandar Shah, who declared himself to be the 'most perfect of the sultans of Arabia and Persia' in 1369 AD, and eventually the khalifa of the faithful, the building of such a mosque was a natural manifestation of his power and wealth. Needless to say, a sultan who could compare himself with the Khalifas of Damascus, Baghdad, Cordova or Cairo could also erect a mosque comparable in size and grandeur to the great mosques of those capitals. It is curious that the Adina Mosque compares with the mosques of those cities not only in size, but also in plan and standardisation; in fact, it rivals the masterpieces of the world. A mosque, described as 'standard', requires a vast rectangular plan with an open courtyard (sahn) surrounded by cloisters (riwaqs) on three sides and the prayer chamber (zullah) towards the qibla. The Adina Mosque conforms to all these principles, and hence is a standard type of mosque.

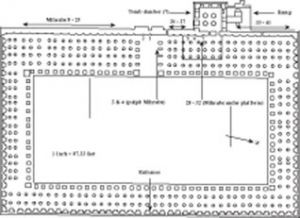

The mosque consists of bricks faced with stones on the lower parts of the walls, and of open bricks on other parts. Its measurement ‘still need to be properly recorded’, but may be approximately accepted as 155 × 87m externally with fluted columns on the corners and 122 × 46m internally with arcade riwaqs by the sides of the courtyard. The 12m wide cloisters on the north, east and south of the courtyard are three aisles deep.

The prayer chamber, measuring 24m in breadth, has five aisles. Dividing the prayer chamber through the middle, a wide vaulted nave runs perpendicular to the qibla wall. It measures 21m × 10m and was once approximately 18m high, but is now fallen. In the absence of a definitive estimate, the domes of the mosque covering squares formed by stone columns have been variously estimated to be 306 and 370. According to Crowe the number is 260. The columns are square at the base, rounded at the middle, and slanting towards the capitals.

The domes carried by triangular pendentives are now fallen except some on the northern cloisters of the prayer chamber. They were of an inverted tumbler shape with an elliptical curve, typical of the dome used throughout the whole sultanate period. The nave, much higher than the cloisters, was covered by a barrel vault, which because of its loftiness dominated the whole structure, and was seen from a long distance.

About the front of the vault much has been speculated: did it hint a rectangular frame like a Persian iwan or was it open to the apex or screenedFoodgrain The design of the cloister arches with abutments at the sides and a cornice suggests that the vault must have had an iwan-portal which would be aesthetically in harmony with the design of the facade. To maintain that beauty and dignity, it also should have had an open arch at the top. Certainly, it would not be congenial in a wet weather land to have such an open and high arch, but to maintain architectural proportions; the architect could not have done otherwise. Clearly realising this difficulty, later architects, such as those in the gunmant mosque of Gaur-Lakhnauti (late 15th c), the Jami Mosque of Old Maldah (1595-96 AD) and its contemporary, the Jami Mosque of Rajmahal, attempted to create screens above the vault arch, but only to destroy its aesthetic qualities.

Covering an area of three aisles depth, on the northern side of the nave and adjacent to the qibla wall, with seven heavy columns at a row, is an upper storey stone platform. This in all probability is the royal gallery (maqsura), meant for the sultan and his entourage when at prayer. There are two doorways on the northern side of the west wall of the platform through which the sultan and his party used to enter. The platform of the gallery must have been screen-parapeted, but have now vanished. The beauty of the gallery at present derives from the ten fluted inner columns, and the three mihrabs in front. Those have been beautifully decorated with carvings, tile-designs and inscriptions in thulth calligraphy. The arches of the mihrabs, carried on slender columns segmented in various designs, are fluted like all the other mihrabs of the mosque in the ground floor. Since the platform is an upper storey of the mosque, it has prompted a higher altitude for this part. This can be noticed from outside due to the higher planes of the domes erected over the gallery.

A beautiful ornamental piece of architecture within the nave to its northwest corner and on the right side of the principal mihrab is the stone pulpit covered by a hooded canopy. About eight of the steps are now gone, but the low-cut abstract relief-designs on its side wall, together with the small mihrab within the hooded part speak of the delicacy of the work of the artisans. The pulpit seems to have influenced some later examples, for example, those in the pulpit of the darasbari mosque of lakhnauti and the bari mosque of Chhota Pandua (dated in the late 15th century on the basis of its architectural style).

A much-discussed adjunct of the Adina Mosque is the so-called tomb chamber of Sikandar Shah at the back of the mosque. The discussion was generated by the discovery towards the beginning of this century of a sarcophagus, probably of a later date, within the floor of the chamber. But that this sarcophagus could not be the tombstone of Sikandar Shah, can be proved by the simple logic of the massive stone pillars running through the middle of the chamber, and the existence of the sarcophagus, not in the middle of the chamber, but towards the west end of the floor.

Tombs of kings generally consist of a single-domed structure with the body of the ruler resting in the middle of the chamber and the dome, signifying the vault of heaven, over him. In the present case, the structure had nine equal-sized domes over it, without any emphasis of a single dome in the middle. But the most important thing to note is that the pillars of the structure carried a stone platform at the level of the royal gallery with two entrances to enter it. A ramp from the west side of the northern space of the platform leading to its top certainly makes it a resting place for the royal entourage before its members entered the gallery for prayers. The so-called tomb chamber was therefore nothing but an antechamber, or a sort of a vestibule to the royal gallery of the mosque. Although no such elaborate chambers are seen in later mosques, small platforms are noticed in the midst of the flights of steps while ascending to the gallery. The two postern doorways flanking the chamber on the ground level in the present case were planned not for the sultan, as was the case in other examples, but for guards or lesser members of the entourage taking their seats on the ground floor of the mosque. The domical platform in the form of a structure with ramp to ascend it on the western side together with a minar near it, makes this side of the mosque more important. Hence lesser care was taken to erect a monumental gateway through the eastern side.

The mosque is now in ruins. The only parts of it that have withstood the test of time are the segments of the west wall, including the back of the vaulted portal. The decorative aspects of the mosque can be ascertained from the structural design of the columns, the pendentives, the mihrabs, the facial terracotta, ornaments of tiles, and the calligraphic inscriptions that can still be noticed in broken condition. The subject matters of other non-calligraphic surface ornamentation are vegetal motifs of local variety, rosettes, abstract arabesque designs, geometrical patterning, and designs of indescribable complexities. It is important to emphasise here that although the ornamental subject matters maintain symmetry in placing and designing, not a single subject is similar to any other in details. The reason, surely, is the creativity of the builders.

The Adina Mosque set an example in mosque ornamentation, both structural and surface. Later examples based on it produced some of the gems of the sultanate architecture of Bengal. [ABM Husain]

Bibliography Abid Ali and HE Stapleton, Memoirs of Gaur and Pandua, Calcutta, 1931; AH Dani, Muslim Architecture in Bengal, Dhaka, 1961;George Michell ed, The Islamic Heritage of Bengal, Paris, 1984.