Shatgumbad Mosque

Shatgumbad Mosque is the largest of the Sultanate mosques in Bangladesh and one of the most impressive Muslim monuments in the whole of the Indian subcontinent. It is ascribed to one Khan al-Azam Ulugh Khan Jahan, who conquered the greater part of southern Bengal and named the area khalifatabad in honour of the reigning Sultan nasiruddin mahmud shah (1435-59). khan jahan ruled the region with the seat of administration at Haveli-Khalifatabad, identified with present Bagerhat, till his death in 1459. Such a magnificent building turned into miserably decaying condition with the passage of time. It is however fortunate that the British government initiated measures for its restoration and repair and the process continued under the direct supervision of the successive Departments of Archaeology of Pakistan and Bangladesh. In the early 1980s an effective long-term programme was undertaken to safeguard this historical monument at the instance of UNESCO, and the work is nearing completion.

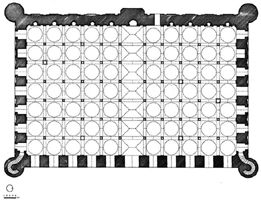

Plan and description Enclosed originally by an outer wall, the mosque is located on the eastern bank of the Ghoradighi, about three miles west of the present Bagerhat town.

The enclosed compound was originally entered through two gateways - one in the east, now restored and repaired, and the other in the north, no longer extant. The eastern gateway, facing cardinally the central archway of the mosque proper, appears to be a monument by itself. It measures 7.92m by 2.44m and consists of an archway having a span of about 2.44m with a beautiful curvature on top.

The mosque proper, built mainly of bricks, forms a vast rectangle and measures externally, inclusive of the massive two-storied towers on the angles, 48.77m from north to south and 32.92m from east to west. The interior of the mosque could be entered through arched doorways - eleven on the east, seven on each of the north and south walls and only one on the west wall, which is placed at the western end of the bay immediately to the north of the large central nave. The interior of the mosque, 43.89m by 26.82m, is divided by six rows of pillars into seven longitudinal aisles from north to south and eleven bays running east to west. Each of the eleven bays, excepting that immediately to the north of the central one, ends with a semi-circular mihrab niche at the qibla wall. The mosque has therefore a total of ten mihrabs. The central mihrab, which corresponds to the central nave, is bigger than its flanking counterparts and shows a rectangular projection on the outer side, carried up to roof level.

The doorway arches of the building are of the two-centred pointed type and spring from the waist of the walls. All the archways of the eastern facade, the central one of the north and south walls and the single one of the qibla wall are set within slightly recessed rectangles. The rest of the archways are formed of two successive arches, the inner one being slightly bigger than the outer one. The outer surface of the walls, except the eastern wall, is variegated with vertical offset projections and double recesses. The battlements and cornices of the building are curved. But unlike the usual curvilinear form, the cornice in the eastern facade depicts a peculiar triangular pediment over the central archway - a device that reappeared in the sadi mosque (1652) at egarasindhur in Kishoreganj.

The four circular towers on the exterior angles are massive and taper slightly towards the top. An open-arched chamber tops each of these towers, rising high above roof level, with a small dome as the crown. The upper chamber of the two front towers has four cardinally set arched windows, while those of the two at the back have only a pair - one on the south and the other on the north. The windows of the rear towers are not exactly in the same axis. It is worth mentioning that each of the two front towers contains inside a spiral staircase of 26 steps, which leads to the arched chamber above. The doorway to the staircase can be approached only from within the mosque. Both the doorways have recently been closed by brick filling. Unlike these two front towers, the rear towers are solid upto the roof level and their arched chambers above could only be reached from the roof of the mosque.

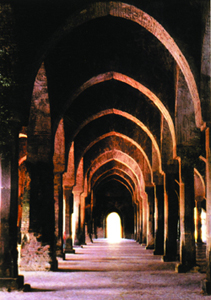

The most attractive part of the mosque is its large central nave, running east to west in a longitudinal line. This nave, consisting of seven independent oblong bays about 4.88m x 3.96m each, divides the interior of the mosque into two equal wings and opens out to north and south by pointed archways. The side wings are divided into square bays, numbering seventy in total. The square bays of the side wings, each measuring 3.96m on each side, are covered with inverted cup-shaped domes, while the oblong bays of the central nave are roofed over with chau-chala vaults. These vaults and cup-shaped domes are carried on intersecting arches springing from the pillars, and the corners between the arches are filled with characteristic Bengali pendentives. The building thus exhibits eighty-one domes in total - four on the corner towers, seventy over the side wings and seven chau-chala vaults over the central nave.

The huge multi-domed roof of the building has been supported by ten rows of pillars, six in each row, running from east to west. The mosque has therefore a total of sixty pillars, the majority of whom were of slender stone, while six were massive, encased either with bricks or sized stone blocks and appear to be original. All the stone pillars, formed of two or three stone pieces one above the other and tightly joined together by a system of plug-holes and iron-craps, must also have been originally massive, with brick or stone casings. The slender stone pillars, depicting square capitals and pedestals with octagonal shafts, have recently been restored to their original shape by an outer veneer of bricks.

The mosque, as recorded by J Westland (1874), was once provided inside with two low brick platforms - one near the central mihrab and the other at the eastern end of the bay close to the north of the central nave. Both these platforms have now disappeared. The platforms, if they originally existed, must have served some purposes, to be explained a little later.

Decoration The decoration of the mosque is mostly in terracotta and brick-setting, and a rare example of stone carving in low relief. Although much of the ornamentation has already disappeared due to the ravages of time, enough still survives in the doorway arches, mihrabs, the angles of the intersecting arches below the domes, the interior of the chau-chala vaults, the raised mouldings of the corner towers, the cornices of the compound gateway and the mosque proper. The cornice of the entire building, the boldly projected band and the cornices of the corner towers are adorned with lozenge patterns. The slightly recessed rectangles, which contain the doorway arches, have mouldings of ornamental bricks in their upper parts, while the spandrels and other parts of the doorway arches are both internally and externally decorated with varieties of designs. The spandrels of the central doorway arch in the eastern facade still depict a pair of large full-blown rosettes and at its key point there is a big perpendicularly placed lozenge which, though now bare, must have been originally decorated like those still intact in the inside of the mosque.

Above the archway are three slightly projected horizontal bands - the lowest one depicts a series of hanging flowers, the middle one shows lozenges alternating with small rosettes and the top one is marked with a series of four-petalled flowers. In between these bands are two slightly sunken narrow panels. The upper panel is enriched with scrolls depicting lotus flowers within loops. The remaining panel depicts a row of tri-lobbed arched niches, which are again ornamented with such designs as palm trees, interlocking squares with small rosettes in the centre and leafy plants with flowers. A beautiful triangular pediment, the ornamentation of which has now completely disappeared, crowns this whole composition. The rest of the doorway arches were also decorated with more or less similar terracotta designs. Inside, the spandrels and upper parts of the doorway arches were mostly decorated with terracotta, the motifs of which vary from entrance to entrance.

The qibla wall is internally embellished with ten ornamental engrailed arched-mihrabs. The central mihrab, unlike its flanking counterparts and those of other buildings of Khan Jahan's period, is entirely made of grey sandstone and its ornamentation is in the Muslim style of carving in shallow and low relief. Most of the decorative motifs have disappeared, but much is still preserved in a decaying condition. The large multi-cusped arch of the mihrab is issued from two faceted decorative stone pilasters. The spandrels of this arch are still depicted with tree motif, which, rising out of the vases, is further marked by branches with leaves and flowers. Immediately above the apex of the arch runs a horizontal band decorated with a row of lozenges alternating with rosettes. The semi-circular mihrab niche is internally divided into two halves by a slightly raised band carved with a frieze of lozenges alternating with rosettes. The upper part of the niche, which takes the form of a half-dome, is carved with rows of rosettes, net-patterns and lotus petals. The lower half of the niche, which is semi-circular in shape, is curved with two horizontal rows of rectangular panels, nine in each row. Each of these panels, being separated from the other by a thin band, shows a cusped arch depicting a rosette in the centre and tree motif intertwining similar small rosettes in the spandrels. From the middle of the dividing band of the niche hangs down a single chiselled chain ending with an oblong pendant. This pendant is depicted with a cusped arch, which has a rosette in the centre and in the spandrels. The mihrab is contained within a broad rectangular border filled with varieties of designs, now in a decaying condition. This rectangular border is topped by a pair of boldly projected mouldings carved with friezes of lotus petals, lozenges and rosettes. This whole composition is crowned in the middle by an inlaid square black stone panel. In the centre of this panel there is a large tiered rosette encircled by seven smaller ones.

The remaining nine mihrabs are entirely made of bricks, showing cusping in their faces. Although much of their ornamentation has disappeared, enough still survives to show that these, not unlike the central mihrab, were originally exquisitely decorated, but with terracotta. The motifs and designs used are primarily the same, but they differ in their arrangement from mihrab to mihrab.

The north and south walls are internally marked with decorative cusped niches, twelve in each wall. Each of these niches is topped by a couple of mouldings. While these mouldings show rosettes alternating with diaper motifs, the space in between is ornamented with floral scrolls in terracotta.

The seven chau-chala vaults over the central nave are internally decorated with a delicate pattern formed by the intersection of rafters and horizontally drawn thin brick-bands, which appears to be an exact copy of the bamboo framework of the chau-chala thatched cottage of Bengal. The frame is further distinguished by lotus flowers in terracotta, each placed on the meeting-point of the rafters and horizontal brick-bands. The brick-setting consisting of horizontal rows of bricks set corner-wise and edge-wise, which serve the purpose of pendentives to support the domes above, is unique and gives an appearance of a delicate carved pattern in high relief. The technique continued to be used widely both for constructional and decorative purposes throughout the Sultanate period and even in several monuments erected during the Mughal period.

Observation The Shatgumbad Mosque at Bagerhat appears to have been the earliest as well as the greatest architectural work of Khan Jahan. From outside, the mosque, with its four heavy and attractive corner towers and seventy-seven domes over the roof, offers a wonderful spectacle to the eye, while its interior is imposing. Architecturally the mosque shows the continuity of the building style that had already been started in Bengal and also some new developments taking inspiration both from the region and from outside. Its bastion-like tapering corner towers with their rounded cupolas and two-storied conception, which rises high above the roof, appears to have been dictated by similar Tughlaqian examples of the Khirki (c 1375) and the Kalan Mosques (1380) at Delhi. The circular shape of these corner towers is worth noting as it distinguishes the Khan Jahani group of monuments from other buildings of Khalifatabad.

The interior plan of the mosque - a large central nave with the side wings - follows a style noticed for the first time in Bengal in the adina mosque (1375), which in turn might have been derived from other earlier mosques erected in imitation of the Damascus Jami (705-15). The chau-chala vaults over the central nave, hitherto not used in Bengal architecture and noticed subsequently in the chhota sona mosque (1493-1519) and the lattan mosque (early 16th century) at Gaur, appear to have originated from the chau-chala huts of Bengal.

The beautiful triangular pediment over the central doorway in the eastern facade may also be said to have been copied from the gable ends of the do-chala hut of the land. Similarly a series of off-set and recessed chases in the outer surface of the walls are likely to have been in imitation of the frame-work of the wood and wattle hut of Bengal.

An important feature of the mosque, though unusual in Bengal but noticed in many congregational mosques in northern India, is a small doorway in the back wall beside the central mihrab, the idea of which might have originally been borrowed from those of early mosques in Islam. In early Islam the postern opening of the mosque is known to have been used exclusively by the caliphs, governors or imams. It is therefore not unlikely that the western doorway of the Shatgumbad Mosque was reserved for Khan Jahan, the governor of Khalifatabad, who had his residence a few yards away to the north of the mosque. Of the two brick platforms, already cited, the one near the central mihrab was perhaps used by Khan Jahan while transacting administrative business, and the other near an eastern doorway was perhaps meant for a religious teacher, who sat on it and expounded Islamic teachings to the people or students. The Shatgumbad Mosque therefore appears to have served triple purposes - a congregational mosque, a parliament or assembly hall like those of early Islam and a madrasa like the Isfahan Jami and the Masjid-i-Jami at Ardistan in Persia.

Origin of the name Literally the term 'Shatgumbad' means sixty domes, but in reality the mosque has eighty-one domes in total - seventy-seven over the roof and four smaller ones over the four corner towers. Two suggestions may be made in this regard. Firstly, the seven chau-chala vaults over the central nave might have given the building the name of Satgumbad (Sat = seven and gumbad means dome), which in course of time has possibly been transformed into Shatgumbad. Secondly, the sixty pillars, which support the huge domed-roof above, might also have originally given the mosque the name of 'Shat Khumbaz' (shat means sixty and khumbaz means pillar). It is not unlikely that the word Khumbaz has subsequently been corrupted into gumbad to give the building the popular name of 'Shatgumbad'. Of the two suggestions the latter seems to be more probable. [MA Bari]

Bibliography Archaeological Survey of India Annual Report, 1903-04, 1906-07, 1917-18, 1921-22, 1929-30, 1930-34; G Bysack, The Antiquities of Bagerhat, JASB, 36, Calcutta, 1867; J Westland, A Report on the District of Jessore, Calcutta, 1874; List of Ancient Monuments in Bengal, Calcutta, 1896; AH Dani, Muslim Architecture in Bengal, Dhaka, 1961; G Michell (ed), The Islamic Heritage of Bengal, UNESCO, Paris, 1984.