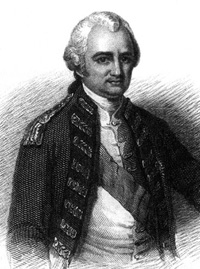

Clive, Robert

Clive, Robert (1725-1774) victor of the battle of palashi and architect of British rule in Bengal. Born in a modest landed family of Ireland and not so distinguished as a student at school, Robert Clive entered the east india company's service (1743) in Madras at the age of eighteen. As a cadet he used to lead a very forlorn and solitary life and suffered periodically from melancholia.

In the Carnatic War, Clive once fell prisoner into the hands of the french and later escaped in guise of a native and reached Fort St. David at Pondichery, which was still held by the English. Clive left the service of the company and joined the Madras army in 1748 as an ensign. He was a turbulent officer, according to his biographer Malcolm; but since violence was mixed with valour in those days, Clive did not find it difficult to get military command in spite of extreme traits in his character. As a lieutenant, he once led an expedition against a Maratha chief and captured Devikut fort in a dangerously adventurous manner. Mill, in his account of Clive’s capture of Devikut fort, accuses him of rashness ‘in allowing himself at the head of the platoon to be separated from the sepoys’. Robert Clive

Clive's next record of military bustle was his Arcot expedition in which he discharged conventional military tactics and made a night attack upon the nawab's fortress, putting the sepoys to flight without the loss of a single soul. Clive's Devikut and Arcot episodes point to his daredevil disposition. With these victories in the south to his credit, Clive received a hero's reception when he returned to London in early 1753. The court of directors lionised him for his victories in the Carnatic War, toasted him as 'General Clive' and presented him with a jewelled sword.

Clive left the army with the intention of becoming a public leader, but failed to get a seat in parliament. Soon he squandered his fortunes through extravagance in social and public life. Disappointed and disgruntled, Clive returned to Madras (1755) in quest of' fortune, and was commissioned by His Majesty's government with the rank of a lieutenant colonel, but the rank was valid for the East Indies only. He came at a time when the French had established their supremacy in south India by entering into a subsidiary alliance with the Nizam who ceded to the French (December 1755) the Northern Sarkars, a district between the mouth of the Krishna and Puri, in Orissa for the maintenance of the French corps. Clive was given the command to chastise the Nizam. He stormed the Nizam's strongest fort, Gheria, captured it (February 1756) and secured the Marathas as allies.

The news of the fall of Calcutta into the hands of Nawab sirajuddaula reached Madras when the company was celebrating the military and diplomatic victories accomplished by Clive. The message came that all English merchants and citizens driven out from Calcutta and other English settlements had taken refuge at Fulta and were 'dying of fever, bad water and scarcity of food'. At this perilous moment, the Madras authorities considered Clive as the most natural choice to lead the rescue operation. The army headed by Robert Clive sailed from Madras on 16 October 1756 and reached Fulta in December. Admiral charles watson headed the supporting naval force. The combined operations of Clive and Watson very easily led to the recapture of Calcutta on January 2, 1757 and to a favourable peace treaty (alinagar treaty, February 9, 1757) with Nawab Sirajuddaula.

The Select Committee of Fort William, which had ceased to exist after the fall of Calcutta, was reconstituted with Robert Clive as governor. In fact, Clive nominated himself to the post. Such self-aggrandizement was challenged by other civil, military and commercial officers who were not inclined to accept him as governor because they felt that Clive was not only an outsider as regards the business affairs of the company in Bengal but also much junior to them in rank and status. roger drake had been in the company's service since 1737 and was the governor until the capture of the settlement by Sirajuddaula. Similarly, Richard Becher was in the service since 1737 and was a senior merchant and officer next in status to Drake. Admiral Watson was senior to Clive in rank and status and in length of service. All were aspirants to the governorship. The dispute was, however, settled by a military threat from Clive and later by an order from the Madras authorities in his favour.

Robert Clive's next moves, after securing his position as governor, were to expel the French from Bengal and thus prepare the pathway to Palashi. He explained to the Court of Directors about the absolute need for replacing the hostile Nawab Sirajuddaula by a pliable one. It was argued that a guided revolution in Bengal's power structure would benefit the company and the English nation commercially and politically. Without waiting for the Court's reply he seized the French settlement of chandannagar in March 1757. After expelling the French he proceeded to eliminate his last and most poweful enemy, Nawab Sirajuddaula. He quickly grasped that there was a clique in the darbar against the nawab and that jagat sheth was its leader. He used Omichand to negotiate a compact between the Fort William Council and the disgruntled Durbar men. The secret treaty of 19 May 1757 was the result. Clive selected Jagat seth from the civil area and mir jafar ali khan, the mir bakhshi or army chief of the subah from the military area as the coup leaders. According to the plan of the conspiracy the so-called battle of Palashi (23 June 1757) was staged. Sirajuddaula was defeated comprehensively and later captured and killed by Mir Jafar's son, Miran.

In evaluating the two events - ouster of the French from Chandannagar and replacement of Sirajuddaula by Mir Jafar - Clive wrote to the Court of Directors immediately after Palashi that the greatest achievement of his life was defeating and ousting the French from Bengal. In terms of the European and global implications of the Seven Years War, he was perhaps right. As for his victory at Palashi, Clive considered it a mere change of nawabs as in Arcot. But soon Clive was to realise that he had, in fact, quietly laid the foundation of an empire in the East.

In the south, Clive's successive victories gave him glory but seldom any financial windfall. In Bengal he gained glory as well as fabulous fortunes. His share in the sack of the murshidabad treasury in the wake of Palashi led him to face a parliamentary inquiry committee at home. Mir Jafar's personal gifts to Clive were staggeringly large. From Mir Jafar he also got a jagir with a large annual income. He retired in 1760 and reached London as the greatest 'nabob' ever returned from Bengal, according to Malcolm, his biographer. In 1762, Clive was raised to the Irish Peerage with the title of Baron Clive of Plassey. Additionally, he was created a Knight of the Bath in 1764. Emperor Shah Alam too adorned Clive with a string of titles which include Dilar Jang (Courageous in Battle), Saif Jang (The Sword in War), Mamiru ul Mamalik (The Grandee of the Empire), Sabdat ul Mulk (The Select of the Kingdom), and so on.

The Palashi event did not bring in a great deal of income for the company as was reckoned by Clive before the episode. Rather, the company, which used to make uniformly great profits from its Bengal trade, was running at a loss after Palashi Revolution. The company's debts were increasing every year. The Court of Directors saw that the company officers had made Bengal a sack of gold for themselves. All of them engaged in private trade without giving priority to the company's business. Clive was sent out again, entrusted with the most difficult agenda: making the company's investment in Bengal profitable.

Clive arrived in Calcutta in May 1765. He had already drawn his policy priorities while on board the ship to Bengal. He was successful beyond his expectation. He went to Allahabad and obtained from the titular emperor the right of diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa for the East India Company in exchange for a regular payment of 2.6 million sicca rupees annually. While taking the post of diwan for the company, he fully discerned its political and administrative implications. The other maritime companies operating in the country with imperial farmans would refuse to recognize the civil jurisdiction of the company, which would mean war whicj must be avoided. Clive also felt that the company had no knowledge of the revenue administration of the country and, indeed, had no manpower to collect revenues from the Bengal villages and markets. Under the circumstances, Clive showed his highest political acumen by restraining himself from administering the country directly. He employed a naib diwan (deputy diwan) in the person of a Persian adventurer, Syed Muhammad reza khan, to run the civil administration on behalf of the company. In other words, under the Clive System, what is commonly known as 'Double Government', the company would extract the revenue of the country without making any investment in terms of money and manpower, and without undertaking any responsibility whatsoever - a perfect deal of income without investment.

This arrangement, from the point of view of the company's interests, was undoubtedly astounding in conception and execution. Even Clive himself could not imagine that his Diwani deal would soon grow into an empire. Clive became a national hero. His life-size statues and busts were raised in many public places including the India Office and Parliament. An indomitable warrior and the architect of an empire, Robert Clive knew no failure in his life except one. It was that he could never overcome his depressive bent of mind. He had shown a suicidal tendency in early life. However, the romance of victories, titles and military glory kept him in high spirits during his Indian career. But after his final retirement in London, when his life became relatively solitary and quiet, the problem revived, and eventually he succumbed to it. On 22 November 1774, Clive shot himself. [Sirajul Islam]