Jatra

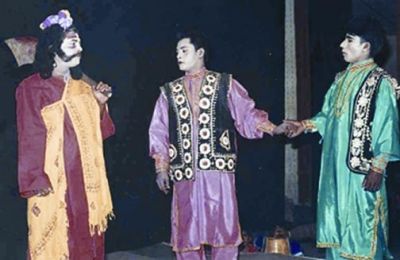

Jatra a form of folk drama combining acting, songs, music, dance, characterised by stylised delivery and exaggerated gestures and orations.

Jatra is believed to have developed from ceremonial functions held before starting on a journey. Other explanations are that it developed from processions brought out in honour of different gods and goddesses. These processions often included songs and dances.Rathajatra , for example, is a festival of this kind.

The jatra may be traced back to at least the 16th century. In Chaitanyabhagavad (1548), Brindavan Das describes a dramatic performance during which Sri chaitanya himself performed the role of Rukmini. Scholars such as Kapila Vatsayan believe this to be the birth of Krishna Jatra. With the development of vaisnavism, Krishna Jatra spread through Bengal.

Krishna Jatra included song and dance, improvised prose dialogue and comic episodes. There were no actresses, and female roles were played by male actors, who were supported by musical and choral accompaniment. The jatra performance was held in open space, on level ground, with the audience seated round the stage. There was no raised platform or curtain. There were occasional exchanges between spectators and performers.

Unlike western drama, there was no dramatic conflict in Krishna Jatra which was confined only to one of the nine classical rasas, the shrngar (erotic). Unlike mangalkavya, Krishna Jatra stressed the individual's relationship with Krishna, which produced different manifestations of love.

Krishna Jatra emerged as one of the leading performance styles in the 17th century. Chandra Shekhar Das, a disciple of Advaita Acharya, is known to have composed a few play-texts of Krishna Jatra, the first of which is titled Harivilas. The deification and immense popularity of Chaitanya led to the emergence of a variant of Krishna Jatra known as Chaitanya Jatra in which Chaitanya appeared as the leading character.

By the 18th century, a number of other forms of jatra had developed: Shakti Jatra, Nath Jatra and Pala Jatra. Krishna Jatra and Chaitanya Jatra, however, continued to dominate. Perhaps the most important developments in jatra during the 18th century were the introduction of comic characters such as Narada and Vyasa, and the gradual secularisation of the form. This change is evident in Vidyasundar Jatra, skillfully adapted from Annada Mangalkavya by Bharatchandra. It is possible that the period also saw the growth of itinerant jatra troupes.

Jatra performances were held in temple yards, public festival sites and courtyards. From the account by Brindavan Das, early performances in the 16th century were given on level ground. The rising popularity of jatra in the 18th century led to improvise raised stages of bamboo poles and planks or wooden platforms. Spectators continued to sit round the stage. Some scholars believe that in the absence of adequate lighting facilities these performances were held during the day. Music and songs continued to dominate. Musical instruments included the Dholak, mandira, Karatal and khol. The adhikari, manager-narrator, played the role of narrator, explaining and commenting on the songs and linking the scenes, often extempore. In the 18th century jatra flourished in Vishunupur, Burdwan, Beerbhum, Nadia and Jessore.

The general social degeneration of the first half of the 19th century was reflected in the jatra, which became increasingly vulgar. In the latter half of the 19th century, Madanmohan Chattopadhyay, instituted a number of reforms. He placed greater emphasis on prose dialogue, shortened the length of songs and reduced their number. He replaced classical ragas with popular tunes. The number of dances was reduced, as well as the number of characters who would dance. Attempts were made to ensure some historical accuracy in costume. Female roles continued to be acted by male actors, but the convention of singing by proxy was introduced. The songs of male characters were sung by mature male singers, while those of female characters were rendered by young actors. Live orchestra incorporated a number of western instruments including the violin, harmonium and clarinet.

Until the end of the 19th century, the adhikari used to write the play. By the beginning of the 20th century, however, jatra texts began to be written by individuals outside the troupe. The adhikari would either buy the text outright or would pay a royalty. Another change that took place at this time was the introduction of the character of Vivek (Conscience).

A major change in jatra took place after the First World War when nationalistic and patriotic themes became incorporated into the jatra. Though religious myths and sentimental romances continued to dominate the jatra, the nationalistic and patriotic spirit of Bengal also found its expression in the jatra. mukunda das (1878-1934) and his troupe, the Swadeshi Jatra Party, performed jatras about colonial exploitation, patriotism and anti-colonial struggle, oppression of feudal and caste system etc. In the 40s, when the struggle for independence from colonial rule was nearing its climax, the socio-political content of jatra superseded the religious-mythical theme. A major change that took place around this time was in the induction of actress to enact female roles.

The Partition of Bengal (1947), however, seems to have adversely affected jatra. Most performances were of historical plays, with a vague sense of nationalism and patriotism, or melodramatic social plays. There was a dearth of playwrights to write for the jatra. But, jatras continued to be performed. Particularly popular during this period, especially in the district of Barisal, was Gunai Jatra, based on the tale of a village maiden named Gunai Bibi. The tradition of religious tales continued, in the form of Bhasan Jatra and Krishna Jatra, both of which were dominated by songs and music.

Jatra today is performed on a rectangular platform (usually, 18' x 15' or 20' x 18'), open on all four sides, about three feet high and erected temporarily for the performance. Musicians sit on two opposite sides of the platform. Spectators sit around the stage, with a section of the space being reserved for women. The whole space is covered and enclosed. About two hours before the performance, between nine or ten in the evening, a stage attendant rings a bell signifying that the show is about to begin. After the second bell, the musicians take their positions and begin playing as a signal that the show is about to begin. Following a fifteen minute break, a third bell is sounded and a fast paced 'concert' commences. This is followed by a patriotic choral song sung by the troupe's dancer-singers. This patriotic choral song was a post-47 feature of jatra in East Pakistan and replaced the earlier tradition of Hindu devotional songs. The patriotic choral song is usually followed by an hour long variety show, incorporating songs, dances and comic interludes. After the variety show ends, around midnight, a fourth bell is rung following which the performance proper begins.

A jatra performance lasts about four hours and is normally divided into five acts, an influence of the 19th century colonial theatre. Following each act, the prompter rings a bell to signal the end of each act. During the intervals between acts, there are songs, dances and comic displays. The performance ends slightly before day-break.

Normally, a jatra troupe consists of 50/60 persons, including actors and actresses, dancers, singers, musicians, technicians, managers, cooks, servants etc. Generally jatra troupes rehearse from the month of Shravan to Ashvin, sometimes to Falgun. Jatra troupes travel from place to place on the occasion of durga puja in the month of Asvin. For this the performance-contracts are signed long before the occasion.

Jatra was an important form of entertainment in the rural society in the past. Nowadays it has been replaced by many modern forms of entertainment. The tastes of audiences have also changed. Under the present cultural environment, the demand for jatra has diminished to a great extent. Jatra performances are therefore being modified. Social and contemporary subjects juxtapose historical and mythological stories. Modern stage techniques are also modifying the manner of speaking, costumes, musical instruments, make up, stage, lights etc. At the same time, contemporary Bangla theatre is drawing upon the indigenous jatra. In place of western, text-based drama, the mixture of dance-song-performance of the jatra is lending a unique strength to contemporary Bangla drama. [Shahida Khatun]

Bibliography SJ Ahmed, 'Drama and Theatre', History of Bangladesh 1704-1971: Social and Cultural History, Sirajul Islam (ed), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 1997.