Muslim Calligraphy

Muslim Calligraphy Bengal under the independent sultans made glorious contribution to the development of arts and architecture as well as calligraphy. Manifestation of the art of calligraphy in Bengal are limited to inscriptions found on the walls of monuments, mosques, madrasas and tombs. Unfortunately, the hostile climate and political turmoil did not permit any manuscript calligraphy to survive.

From the very beginning, the style of calligraphy in Bengal was characterised by delicacy of form and subtlety of arrangement. The features may be traced back to the famous inscription of Bari Dargah in Bihar, which was once part of Bengal. In spite of the general similarity of its style with that of the inscriptions of the Qutb Minar and the Quwat-ul-Islam Mosque in Delhi, there is a tendency of the scribe to flourish the ends of some of the vertical letters downward slantingly and to ligate the tops of some of the upright letters to form, what may be called, a sort of noose to enhance the beauty of the entire text. These tendencies were successfully developed and brought to perfection in the later calligraphic inscriptions in Bengal.

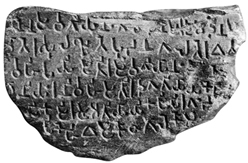

Inscriptions dated 647 AH/1249 AD, found in the back wall of a mosque of Gangarampur, West Dinajpur, show letters beautifully executed with slight vertical flourishes which was to feature prominently in the later Tughra style of Bengal. Specimens of Naskh calligraphy of unsurpassing elegance is found in an inscription dated 701 AH/1301 AD in Bihar. It records the name of Sultan shamsuddin firuz shah. The tendency of ligating the tops of some vertical flourishes, as has been noticed in the Bari Dargah inscriptions, is carried to perfection here. The calligrapher has shown great command in drawing the vertical lines and curves, which though precise and crisp, are absolutely free from conventional restrictions. Compared with the calligraphy found in the contemporary inscription of the Alai Darwaza at Delhi, this one discloses the fact that the keynote of the Bengal style was delicacy and refinement, while the aims of Delhi art under the early sultans were strength and grandeur.

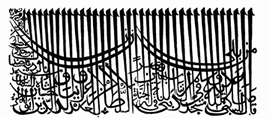

Another inscription dated 713 AH / 1313 AD of Firuz Shah of Bengal, found on the northern side of Zafar Khan's Tomb at Tribeni, shows a kind of calligraphy that marks a further development towards a variety of Tughra. The characteristic features of this kind of Tughra are vertical flourishes arranged in uniform and regular patterns where the horizontal letters are clustered at the base. The isolated fi and detached kaf placed across the vertical shafts are also noteworthy.

The process that started with the Firuz Shahi inscription at Tribeni was carried to perfection in an inscription of Sultan Shamsuddin iliyas shah that can be read in a modern mosque in the eastern suburb of Calcutta. Here the letters at the base, forming almost ringlets, are artistically intertwined. Then the vertical flourishes are arranged elegantly in the shape of a row of spears. The isolated fi and detached Kaf placed across the vertical shafts of some letters appear more elegant. Hence the calligraphy of this inscription may be described as a variety of the fully developed Tughra.

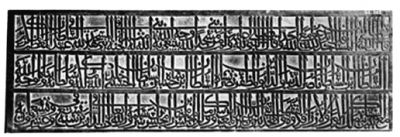

The inscription dated 776 AH / 1374-75 AD found in the adina mosque at pandua exhibits calligraphy that stands as a landmark in the development of calligraphy in Bengal. The remarkable calligraphy of this inscription impressed blochmann so much that he remarked, '(They) are the finest I have seen. The characters are beautiful and the rubbings have created a sensation whenever I have shown them'.

Two features of this calligraphy deserve particular attention. First, the carefully drawn sidewise slanting flourishes of the vertical shafts that appear like edges of arrow, which hint at some characteristics of the ‘Bow and Arrow’ variety of Tughra, developed later in Bengal.

Secondly the later fi, which appeared in earlier inscription as isolated, is elegantly drawn here across the vertical shafts of some letters like a floating swan. The second feature constitutes the main motif of a variety of Tughra described as the Swan variety.

Another inscription of the same mosque displays an equally elegant style of calligraphy. The top line of its panel is written in beautiful Kufic. It seems that calligraphers of Bengal could write in Kufic effectively. But it appears to be the only specimen of Kufic style found in Bengal.

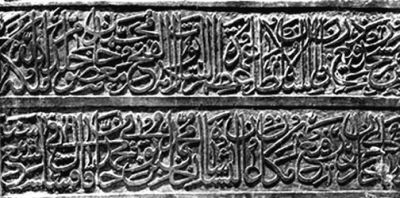

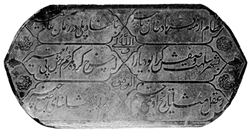

A fruitful outcome of the patient experimentation is the calligraphy of the inscription dated 847 AH / 1443 AD, found at Baliaghata. It belongs to the reign of Sultan nasiruddin mahmud shah with whom the second phase of Iliyas Shahi rule began in Bengal. This inscription leads directly to the period when the development of calligraphy in Bengal attained its highest peak.

The fully developed Tughra form used in this inscription shows a very intricate and artistic pattern. The shaft of the vertical letters are raised upwards and arranged elegantly in a row while the main text is set in order at the base. The round letters are further twisted to form themselves into many ringlets. Except for the variation in motifs into which the letters are formed at different times this remains the standard pattern of Tughra calligraphy in Bengal.

A definite step towards the development of the 'Bow and Arrow' variety of Tughra was taken in the inscription dated 878 AH / 1474 AD. This belongs to the reign of Sultan shamsuddin yusuf shah. But the perfection of the 'Bow and Arrow' variety of Tughra took place in the reign of Saifuddin Firuz Shah II (AH 893 / AD 1487). The inscription of Katra Mosque, near Malda, is a perfect example of the 'Bow and Arrow' variety of Tughra.

In short, at least five kinds of Tughra were developed in Bengal. They are Plain Tughra, Tughra with detached Kaf and Ya, Tughra with detached letters like ha, Ya hung on the high vertical shafts, the swan variety of Tughra, and the most famous of them all, the 'Bow and Arrow' variety of Tughra. In the latest phase of their development the salient features of all these Tughra styles are combined to evolve a new kind of simple but very elegant Tughra as may be seen in the inscriptions of the Husain Shahi period. The varieties of Tughra style developed in Bengal seem to have no parallel in the entire Muslim world.

A part from developing the varieties of Tughra the calligraphers of Bengal were always capable of writing in simple but elegant Naskh and Thulth. An inscription dated 889 AH /1484 AD found in the gunmant mosque at Gaur exhibits Naskh calligraphy of the highest order.

Towards the end of the Husain Shahi rule in Bengal, along with socio-political disorder, decadence affected artistic activities. During the short-lived Afghan supremacy in Bengal, the art of calligraphy appears to have been revived for a short while, as may be seen in the inscription dated 967 AH / 1559 AD belonging to the reign of Ghiyasuddin Bahadur. Soon, however Bengal lost its distinct kind of calligraphy. After the Mughal occupation, Bengal calligraphers began to imitate the styles that were practised in the capital of the Mughal Empire. [PIS Mustafizur Rahman]