Ornaments

Ornaments have been used from prehistoric times and for a variety of reasons. In addition to their aesthetic or seductive charm, ornaments represent savings, are used as status symbols, declarations of identity and beliefs, or signs of marital situations.

In India and Bangladesh, jewellery has been the traditional form of savings, with gold jewellery being prized because it can be easily converted into money. Ornaments are often associated with magical or religious properties and worn to ward off evil or to bring prosperity. They are made from a variety of materials, from flowers, feathers, teeth, shells to silver, gold, pearls and diamonds.

In the subcontinent, jewellery dates back to 4000-3000 BC. Excavations at the Indus Valley sites have unearthed bronze, silver and gold ornaments. Hairpins, earrings, necklaces, bangles, finger rings were fashioned out of metal and studded with stones. Bead jewellery was also popular. The Aryans were fond of gold ornaments, and the Yajurveda testifies that gold had magical powers. Brahmanical texts laid down strict rules about differing types of gold ornaments for different people. The Kamasutra mentions 64 arts, including the knowledge of gems, the art of stringing garlands and necklaces, of making ear ornaments, and using jewellery. Men and women were advised to brush their teeth, apply perfume and put on some jewellery. However, when their husbands were away, virtuous wives were cautioned to wear only auspicious jewellery. When a man wished to express his feelings for a woman, he was advised to give her presents of ornaments such as earrings and finger rings.

The ramayana gives an account of the jewellery of the 4th-6th centuries, much of which is still used today. Among the articles mentioned are jewelled rings, golden chains, conch shell bangles, necklaces, diadems and golden crowns. Hanuman carried rama's ring to sita to prove that he was Rama's messenger, and carried back from Sita a hair ornament made of pearl.

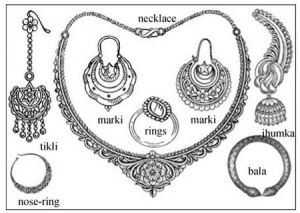

Mughal kings were fond of using jewellery, and English travellers note the lavish use of jewellery at court. Under the Mughals the art of setting stones in precious metal attained a peak of perfection. Some ornaments still in use today, such as the jhumka and the tikli, may be traced to the Mughals whose miniature paintings often show the use of these ornaments. The fondness of the Mughals for pearls is evidenced by these paintings, many of which show ornaments being set off by strands of pearls. The jhumka, for example, is held by strands of pearls, which relieve the wearer of the weight of the ear ornament.

With the advent of the British and the fall of the Mughals, there was a change in taste as well as a different reason for buying ornaments. Gems lost their appeal and people put their trust in gold ornaments, which could always be sold. Many old jewels found their way as booty to the coffers of Englishmen and were reset in new ways. English designs also started influencing Indian jewellery. Indian jewellery previous to European influence used table diamonds and stones with smooth edges. With the new demand for multifaceted stones, cut and set European fashion, the earlier setting of rounded stones into gold, known as the kundan setting, was replaced by the 'claw' setting of cut stones. However, with the reawakening of a nationalist spirit towards the middle of the 20th century, older, more elaborate forms and more affluent and ostentatious than the earlier Swadeshi spirit were sought once more.

The history of development of Bangladesh ornaments may be divided into four phases: 1000 BC to 1200 AD; 1200-1750 AD; 1750 AD-1950 AD; and 1950-2000. At the same time, it should be noted that many pieces of jewellery in use in Bangladesh today can be traced to origins in the past, and that a wedding set today may not be very different from a Mughal ornament. In other words, different styles and influences co-exist at the same time. Furthermore, while gold jewellery has felt the impact of change, the old traditional forms are in silver and heavy wedding ornaments remain the same from one generation to another, the contemporary handicraft shops create new designs in silver.

The earliest examples of ornaments found in Bangladesh date back to about 1000 BC, the estimated date of beads made of semi-precious stones found at Wari-Bateswar, northeast of Dhaka. Stone beads have also been excavated at Mahastangarh. Few examples of actual ornaments survive. Knowledge of early ornaments of Bangladesh therefore derives from ancient sculptures in stone and Terracotta. The terracotta plaques of paharpur and Mahasthangarh reveal the type of ornaments worn in this region during the 6th to 8th centuries.

Both men and women used to wear jewellery: earrings, armlets, bracelets were common to both sexes. Women wore anklets. While the ornaments depicted in terracotta are often plain pieces, black stone carvings show ornaments of intricate detail. A 10th century statue of Marici in the bangladesh national museum shows a variety of jewellery of delicate workmanship: an elaborate head ornament, two pairs of armlets, bracelets, two necklaces, anklets and earrings. The earrings are round studs with a small rosette in the centre. The short necklace, as well as the armlet, has leaf motifs. The broad bracelet shaped to the wrist has an open latticework design. The longer necklace is composed of round beads, possibly pearls. At her waist, Marici has a girdle. Compared to the girdles shown on other statues, Marici's girdle is fairly simple.

Many different forms of girdles are represented on statues. Early examples are a simple string of beads. Later representations are elaborate, with several strings looped up at intervals. One fine example of a girdle is displayed on the statue of the goddess Gauri at the Bangladesh National Museum. From a waist belt hang three appendages, all elaborately ornamented with eight-petalled lotus motifs and four-petalled flowers. On both sides are rows of round beads. Four strings of beads, two comprising smaller ones and two larger ones, are looped and caught up at intervals.

The advent of Muslims did not bring in any radical change immediately. Contemporary writings record continued fondness of both sexes for jewellery. Both men and women wore finger rings and earrings. Men started wearing turban ornaments as well. Women wore bangles, variously called bala and kankan, necklaces consisting of five to seven strings of gold beads, called satesvari, rings on all ten fingers, and anklets of silver. Muslim men of 16th century Bengal carried silver daggers.

Gradually the influence of the Mughals filtered down to Bengal and may be seen in the jewelled sets of nawabs and zamindars. While the lower and middle classes believed in gold as a means of saving, affluent Muslims acquired ornaments for their beauty, frittering away money on enameling, stone encrusting, and carving of precious stone with verses from the quran. Some fine jewelry belonging to the nawabs of Dhaka shows the influence of the Mughals as well as of European designs. An album of 14 pieces of jewellery in the Dacca Collection published by a famous Calcutta jeweller, Hamilton and Co. reveals how Mughal tastes were merging with European tastes among the rich nawabs.

The Dacca Collection has eastern ornaments like armlets, called variously dastband and bazooband, a serpaitch or turban ornament, a jewelled fez, as well as of western ornaments such as buckles and brooches. One of the dastbands in the collection is made of Indian table diamonds and has a centre stone known as daria-i-noor or River of Light, which was believed to have belonged to the Shah of Persia. Another bazooband comprises emeralds and diamonds. The use of ornament as amulet may be seen in this piece of jewellery with the central emerald being engraved with verses from the Quran and the side emeralds with the word 'Allah'.

Earlier Indian jewellery had been body ornaments worn on bare parts of the body, but now the western style of wearing ornaments on clothes became popular. Brooches and clasps became fashionable among high-class women. An example of the new taste may be seen in the ornament known as the 'Rose of Cashmere' and a star pendant belonging to the Dacca Collection. The Rose of Cashmere is a rose spray composed of brilliant cut diamonds with a central ruby, behind which was a container to hold a miniature Quran. The star pendant was also set with brilliant cut diamonds showing the European influence.

With the troubled times that heralded the partition of India, gold ornaments became popular once more. But with peace the trend changed. In West Pakistan stone setting was popular and the taste in East Pakistan among the upper middle class followed suit. Nauratan (literally nine stones) sets became popular. The mid-1960s also saw the emergence of the pink pearl in East Pakistan. Minute pink pearls set in gold became fashionable.

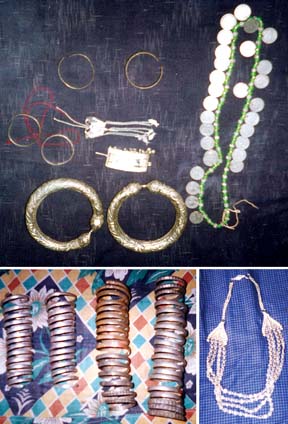

Today in Bangladesh a number of trends in jewellery may be seen at the same time, partly because of changing tastes, partly because of high costs. With the exorbitant price of gold, designs have changed as well. Because value is still given to gold and because during weddings at least one set of ornaments must be given by the bride's family, jewelers adapted to the times by beating out designs in filigree work so that a set may be made with the minimum amount of gold. However, there is also growing affluence among a portion of the population, so fairly heavy traditional ornaments of gold as well as naoratan sets are also being made to cater to this demand.

At the same time, partly because of feelings of national identity and pride, rapid urbanisation and growing insecurity, many women are giving up the traditional chain, bangle, and earrings of gold and opting for more traditional forms of ornaments in silver or even copper and brass. Handicraft shops like Arong, Kumudini, Aranya, etc all have jewellery counters where ornaments made from silver and copper, as well as terracotta and seeds, juxtapose ornaments of semi-precious stones and pink pearls. Traditional silver ornaments such as makri earring or heavy tribal jewellery from the chittagong hill tracts, traditional amulets, such as the maduli and ta'abiz threaded on black string are coming back into fashion. In cox's bazar, ivory or bone ornaments are popular as are khonta mala, serrated round hollow beads strung on black thread.

Ornaments worn for religious reasons include the pola, red coral bangles, the conch shell or shankha bangle, occasionally ornament with gold wire, the iron bangle (worn ostensibly for the husband's well-being), and rings made of the traditional eight metals. Among affluent Muslims, wearing gold pendants with 'Allah' written in Arabic is popular, as is the use of small lockets to hold a miniature Quran. Traditionally, married women wear bangles, but, with increasing insecurity, many are giving up gold bangles for artificial ones. [Niaz Zaman]

Bibliography JJ Bhusan, Indian Jewellery and Ornaments, Bombay 1964; Dacca Collection, Hamilton and Co., Calcutta.