Jute Industry

Jute Industry Manufacture of jute goods was the single largest industry of Bengal under British rule and east Bengal (ie erstwhile East Pakistan) during the quarter century after 1947. After the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent state the contribution of the industry to the nation's GDP and in the field of employment declined (in absolute and relative terms). But still it plays a significant role.

The first jute mill was established at Rishra on the river Hooghly, north of Kolkata in 1855 by George Auckland together with a Bangali partner, Shyamsunder Sen. Jute had been produced in Bengal since ancient times, but prior to 1855 the fibre was locally used by the handloom weavers to make twines, ropes and coarse fabrics for the poor. The impetus behind the establishment of a jute-based industry came from Dundee, Scotland. Frequent naval blockades during the Napoleonic wars resulted in erratic supply and high prices of Russian flax and the mills in Dundee started examining the possibility of using jute as a substitute. However, there was a technological problem. As coarse and brittle fibre jute needed to be softened and strengthened before it could be used for high speed spinning and weaving. In 1832 the firm of Balfour and Melville overcame the problem by sprinkling raw jute exported from Kolkata with suspension of whale oil and water. The new process was put to test in 1838 when the Dundee mills were a awarded a large Dutch order for manufacturing Javanese sugar bags. The jute bags were accepted and burlap came to stay. This helped establish jute in the eyes of cloth and bag manufacturers, thereby giving a fresh impetus to the industry. However it was the Crimear War (1854-56) which really set the jute industry on a strong footing.

At a time when the volumes of world trade was increasing at five per cent per year the Dundee mills could not sit idle, especially when a commercially viable alternative fibre was available from a colony. The American Civil war (1861-65) gave a further impetus to the substitution process. For the supplies of American cotton became much restricted at a time when trench warfare increased the Union’s and the Confederacy’s requirements for burlap sacks and sandbags. In both cases the industry acquired new users who did not return to flax and cotton when these fibers became once again available. The main factor behind this permanent shift was the comparative cheapness of jute.

Thus, when the first jute mill was set up in Bengal, Dundee mills were already well-established and opening up new markets for their products. But the Kolkata industry made rapid progress once it started its journey. The number of mills increased to 18 in 1882 and 35 in 1901 with 315 thousand spindles, 15 thousand looms, 110 thousand workers and a paid-up capital of 41 million rupees. Over 85 per cent of the produce was now being exported to the important Dundee preserves - Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Thus by the end of the nineteenth century jute industry became the second largest (the first being the cotton textiles) in the sub-continent and Kolkata became the world's most important jute manufacturing center. Incidentally all the jute mills were established in and around the metropolitan city and controlled by the foreign capitalists. Bengalis were not at all in the picture though, as mentioned earlier, one of them had the partnership in the establishment of the first jute mill. Such a phenomenal rise of Kolkata in the field of jute manufacture was due to a combination of several favourable factors - lower labour cost (by about 1/3), proximity of the source of supply of raw jute, longer working hours and better quality of products.

Progress in the jute industry was even more impressive during the first three decades of the twentieth century. While the number of jute mills increased from 38 in 1903/04 to 98 in 1929/30, production capacity in terms of the number of installed looms went up three times and the number of persons employed in the industry from 123,689 to 343,257. This was primarily due to the high profitability of investment resulting from rising world demand for jute goods. The world demand increased by 300 per cent during 1895-1912 and it went up even further during the war years. To this was added another favourable factor ' restrictions placed by the government on the import of machinery and mill stores. The outcome was that increased demand for jute goods had to be met by existing mills in Bengal which placed them in a strong position to bargain. Thus, a combination of increased world demand for jute goods and restriction on production capacity enabled the jute mills to earn profit at a high rate, the index of net profits rising from 100 in 1914 to 570 in 1917. This prosperity did not last long. But the investment in jute mills continued to be significantly profitable and this brought about large extension after the war. Between 1920/21 and 1929/30 as many as 21 mills came into existence and by 1930 total number of looms increased to 54000. Side by side working time was increased from 54 to 60 hours a week.

Just at this time when the industry had created additional production capacity, the Great Depression hit the world economy. Demand for and the price of jute goods drastically declined and the Indian Jute Mills Association (IJMA) reacted by reducing the working time to 40 hours and sealing 15 per cent of the looms. But these steps failed to improve the situation and between 1929/30 and 1934/35 a total of 83000 workers were thrown out of employment. The causes for this failure are not far to seek. Firstly, foreign countries imposed heavy duty on the import of jute goods to protect their own industry. Incidentally in 1940 Kolkata mills accounted for 57 per cent of the total number of looms, the rest being outside the sub-continent. Secondly, non-IJMA mills increased their share of the production by working 108 hours a week. Thirdly, during the first five years of the depression more than 18% of the gunny bags were produced on account of free riding and cheating by the non-member mills. The IJMA had always acted as a quasi-monopolistic organisation to protect and uphold the interest of its members. But under the changed circumstances it now failed to perform the duty. At the same time it failed to persuade the government to legislate to make the non-IJMA mills comply with the restrictive practices.

The IJMA had now no option but to increase production. Consequently prices of jute manufactures fell to its lowest level and the rate of profit which was 86 per cent in 1929 (1928=100) now declined to 12 per cent in 1937. The recession came to an end with the outbreak of the World War II which generated a massive demand for sandbags. Although the mills could not depress raw materials prices as effectively as it had done during World War I, they still earned handsome profits. Net profit shot up from seven per cent of the paid-up capital in 1935-38 to 52 per cent by 1942 and remained above 40 per cent from 1941 to 1945. Consequently, the rate of increase in the establishment of new jute mills which had slowed down during the depression years now picked up and in 1945/46 the number of jute mills in the province stood at 111with 68.4 thousand looms.

One significant development in the jute industry during the last quarter of the British rule was the increasing entry of Indian, especially the Marwari entrepreneurs in this field. Ten jute mills were established by the Indians during the 1920s and most of these were owned by the Marwaris. At the same time through the purchase of the shares the Marwaris also entered the boardrooms of the British companies. By December 1930, 59 percent of the foreign firms had Marwari directors. They increased their share to 62 per cent in 1945 and 82 per cent in 1945. Yet another important development of the first half of the twentieth century was that jute industry gradually became more broad-based. By 1890 the output of the Kolkata mills equaled the products of Dundee mills. Dundee gradually lost her importance even further in the subsequent years. For while in 1940 Kolkata mills accounted for 57 percent of the total looms, mills in Germany, Italy, Belgium, France, South and North America accounted for 28 percent and Great Britain only seven percent.

Needless to mention increased demand for raw jute from home and abroad led to a vast expansion of jute cultivation in Bengal, from a meagre 19 thousand acres during 1845-1850 to 29 million acres in 1901/02. In the subsequent years jute cultivation declined but still it stood at 20 million acres in 1945. However, though raw jute production was largely a monopoly of Bengal, most of the jute cultivation was in the eastern part of the province. True, one of the early mills was established at Serajganj in Pabna district but it was found unworkable and when it was damaged in 1897 by an earthquake its machinery was brought to Hooghly to be installed in Delta Jute Mill. In the first half of twenty century there were rumors about the establishment of a jute mill at Narayanganj, but no step was taken in this direction till the early 1950s. Thus, the situation was such that though all the jute mills were located in western Bengal, eastern part contributed most of their raw materials. The causes for this phenomenon are not far to seek. Firstly, jute was an export-oriented industry and therefore needed an outlet. But such an outlet was not present in east Bengal except through the port of Chittagong which was under-developed. Secondly, jute industry needed heavy machinery and stores and the cost of sending them to any east Bengal district from Kolkata was going to be high. Thirdly, the mills in Hooghly had the advantage of being situated near the coalfields of Raniganj. Incidentally, it should be mentioned that the price of electricity was higher in the towns of east Bengal than in 'Greater Calcutta' areas. Finally, Kolkata had the advantage of being the capital city. Such factors precluded the possibility of the development of jute industry in eastern Bengal.

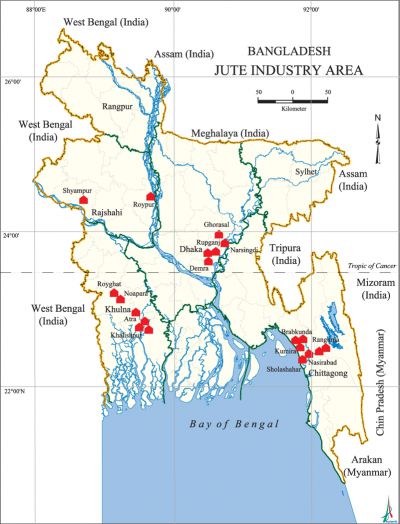

After partition in 1947 India and Pakistan became totally dependent upon each other. For, while all the jute mills were located in the former, 80 per cent of jute growing area was in the latter. In other words, while India had to import most of the raw jute needed to keep her mills operational, Pakistan faced the problem of the disposal of her raw jute. In the circumstances the two countries signed an agreement in 1947 allowing free movement of goods across the border. This agreement lasted till 29 February 1948 when India declared Pakistan a foreign country for the purpose of trade and custom tariffs were applied to Pakistan. Thereafter Pakistan entered into various trade agreements with India, but the latter failed to lift the agreed quantity of raw jute. Domestic availability of raw jute, the higher value-added in manufacturing and the prospect of employment of surplus labours are made it desirable for Pakistan to develop her own jute industry. But the uncertainty of export trade added an urgency in this respect and the first jute mill - Bawa Jute Mills Ltd - started production in the middle of 1951. The second mill - Victory Jute Products Ltd - went into production towards the end of the same year. These were mills in the private sector. The third mill that went into production in the same year was the Adamjee Jute Mills and this was set up in co-operation with the Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation. Thus the pattern of development in active co-operation between the government organisation and private entrepreneurs was established and by 1960 out of 14 mills 12 were initiated by Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation. These 14 mills had 5700 employees 7,735 looms and produced 2,60,393 metric tons of jute goods is 1959/60. Development of jute industry proceeded very fast during the subsequent decade and by 1969/70 East Pakistan had a total of 77 jute mills with a little over 25 thousand looms and a consumption capacity of 34 lakh bales of raw jute. In that year the number of employees in all the jute mills stood at 170 thousands and 77 crores of rupees were earned through the export of jute goods to 120 countries of world. Thus, East Pakistan became the biggest exporter of jute goods. In 1952/53 export of jute goods had accounted for only 0.2 per cent of the total foreign exchange earned by Pakistan. Its share increased to 46 per cent in 1969/70.

While private investors in the jute-manufacturing sector during the 1950s had been the non-Bengalis, some Bengali entrepreneurs began to show interest in this field in the early 1960s. These Bengali entrepreneurs were individuals who until then had been engaged in trading or small-scale industrial activities and by then had accumulated some capital. Moreover, the predominance of industrial investment in East Pakistan by non-Bengalis gave rise to strong resentment and its continuation was no longer politically acceptable. It was basically in the light of such a situation that government became concerned about the need for promoting Bengali participation in the industry. In line with this the late AK Khan, Minister of Industries under the Government of Pakistan, took the initiative of dividing Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation into two parts - one for the East and the other for the West Pakistan. He also adopted the policy that 250 looms mill was viable. (Earlier the requirement was 500 looms). A Bengali entrepreneur or a group with a capital of 25.00 lakh (or a bank guarantee for the same amount) was allowed to set up a jute mill in association with the East Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation (EPDIC). This arrangement enabled the Bengali entrepreneurs to establish, by 1970, 41 jute mills with about 11,500 or 32 percent of the total looms of various categories. The development of such a large jute industry within a span of only two decades was a remarkable phenomenon. What was even more remarkable is that the one-third of the industry was now owned by the Bengali entrepreneurs who were almost unknown in the early 1950s.

After the emergence of Bangladesh as in independent state the government asked the Jute Board to take over the management of the jute mills which belonged to the non-Bengalis and who had fled the country. The Jute Board was obliged to manage these mills either directly or through the appointment of Administrators. But the Administrators were appointed mostly on political considerations, without taking into account their managerial ability. Then in March, 1972 the government nationalised all the mills in the different sectors of the economy of the country. The mills owned by the non-Bengalis had to be taken over because they were now foreigners, but the decision to nationalise all the mills was taken in the name of socialism enshrined in the constitution of the Republic. The management of all the nationalised mills was entrusted to the different Corporations and the Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) was given the responsibility of running the jute mills. The Corporations was going to be headed by a Chairman with the rank and status of a Secretary to the government. The BJMC gradually took over the responsibility of centralised purchase of raw jute, sale, finance, appointment, promotion, transfer and decision-making powers. But mismanagement started from the inception. Financially, as Taka was devalued to the extent of 66 per cent, the BJMC incurred a loss amounting to Tk 60.19 crores per annum during 1975/76 to 1978/79. The operating loss was mainly due to the increased cost of raw jute, higher prices of stores and spares, increase in wages and salaries and rampant corruption. With the change in government in 1975 an Expert Committee was appointed to make an in-depth study of the problems faced by jute industry. The Committee stated that the losses of the mills were due to a) deterioration in the morale of the officers and workers b) inadequate supervision at all levels of the administration, c) complete absence of motivation and sense of belonging and d) non-accountability of the executive functionaries. Such weaknesses which were more or less common in all other nationalised sectors were not surprising, given that socialism was introduced without the necessary ideological preparations.

As per the recommendations of the Expert Committee the process of de-nationalization started in 1979/80 when three Bangladeshi-owned yarn/twine jute mills were returned to their owners and three other such mills were sold/auctioned to Bangladeshis. Then the government freed investment in private sector for setting up of such mills with the import of second-hand machinery. In 1982 the government handed over 35 jute mills to their former Bangladeshi owners. During 1982-84 some of the jute mills is the private sector (represented by BJMA ie Bangladesh Jute Mills Association) made profit, but thereafter these mills incurred losses as did the mills under BJMC.

The reasons for such losses, part from those mentioned earlier, were a) reduction in the price of jute goods by India, b) enhanced a power tariff and c) increase in the wages of the workers. Against this cost escalation the government paid Tk 135.79 crores during 1986-89 as Export Performance Benefit and Tk 255.42 crores as cash subsidy during 1989-92. In 1990 the World Bank suggested to the Bangladesh government to undertake a study on jute industry. The government appointed a foreign consultant to carry on the study in association with a local Chartered Accountant. The study reported that the cumulative liability of the jute mills to banks as in June 1991 stood at Tk 2075.32 crores of which Tk 1299.05 was against BJMC mills and Tk 774.27 crores against 35 de-nationalized mills. The study recommended that the excess production capacity and the excess (ghost) work forces should be removed and the mills under BJMC should be privatised. The World Bank offered a credit of US$250.0 millions to implement these and several other recommendations. The Bangladesh government accepted those recommendations - it closed down four mills and provided fund to against export loss and financial assistance to the BJMC mills for the removal of excess labor force. But despite the implementation of the World Bank recommendations during 1992-95 the mills under BJMC and BJMA did not attain commercial viability and these continued to incur loss - during 1991-2000 a total of Tk 1895.40 crores by the BJMC mills and Tk 695.55 crores by the BJMA mills. In June 2002 the government closed down the Adamjee Jute Mills which was the largest in this sector. The experience of the recent past has been the same. The mills under BJMC incurred losses to the extent of Tk 1911.00 crores during 2001/02 to 2006/07 periods. The mills in the private sector have not been doing well either - in 1998 out of 41 jute mills in this sector three were closed and two laid off. Upto December 1999 these mills have accumulated losses of more than Tk 12 billion. Thus, privatisation itself does not seem to offer a solution to the problems faced by the nationalised industries.

Jute industry in Bangladesh has been facing several problems over the years: a) increase in the cost of productions in the face of the stagnation or decline in export price, b) decline in productive efficiency of machine which have now became old, c) labour problems, d) widespread corruption, e) inefficient management and the consequent accumulation of huge operational losses. In other words due a whole range of factors a vibrant industry of the past is now being regarded as a 'sunset' industry and the golden fibre has lost of much of its shine. Still the jute industry must be said to be playing an important role in the national economy: it provides direct employment to about 150 lakh people even after the closure of 40 per cent of its production capacity, pays over Tk 100.00 crores for insurance and similar amount as cost of internal transport of raw jute, earns about Tk 150.00 crores worth of foreign unchanged and consumes 30 lakhs of raw jute, thereby benefiting millions of jute cultivators. [Mufakharul Islam]

Bibliography Azm Iftikhar-Ul-Awwal, The Industrial Development of Bengal 1900-1939 (New Delhi 1982), Omkar Goswami, Industry, Trade and Peasant Society: The Jute Economy of Eastern India, 1900-1947 (New Delhi 1991); M Serajul Huq Khan, Bangladesh Jute Industry (Post Liberation Episode)