Kalighat Painting

Kalighat Painting developed and thrived in the nineteenth century at the market place around the Kali temple, Kalighat, in Calcutta. Kalighat painting originated as a souvenir item associated with the Kali temple of Kalighat. Initially, it dealt with Hindu mytho-religious themes. Gradually, it embraced secular themes and commented on contemporary social affairs, which until then had been beyond the purview of the art of pilgrimage centres.

It reflected and documented the ethos of a newborn urban society. The artists also painted Duldul (Imam Husain’s horse) and other subjects for their Muslim clientele. It soon became a school with the capacity of assimilating exotic elements and modifying itself to create a new and vibrant visual language. The present Kali temple was built during the early nineteenth century. A market too developed around the temple. Traditional Hindu image-makers migrated to Kalighat from different districts of Bengal. The area where these people settled came to be identified with their profession, as Pata-Pada, or Artists’ Locality.

Initially, a part-time vocation, for the painters, they started to paint icons of the Hindu deities on paper on a full-time basis because of the growing demand. Mrs Belnos, a European painter reported in Manners in Bengal (1832) that she saw ‘a few ill-executed paintings’ depicting native gods, hanging even in the houses of people whose earnings just enabled them to sustain themselves.

A sketch by her of a Bengali home shows a Kalighat painting. These painters who came from different areas of rural Bengal reacted to the urban culture and norms and spontaneously recorded the happenings of their times.

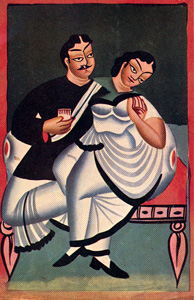

Thus in one type of secular painting they derided Baboo culture, feminism, social debauchery, religious hypocrisy, and all types of falsehood. In such paintings the artist became a social commentator. An artist would sell between 16 and 64 paintings per rupee. Not surprisingly, then, their work found a ready market among middle and lower-middle class people. The Indian intellectuals of that time despised everything that did not conform to their Victorian ideal. It was left to Rudyard Kipling to be charmed by the terse beauty of the art and to acquire a lot which was to be donated in 1917 to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This collection and the Prague Museum collection constitute the best remaining specimens of Kalighat painting.

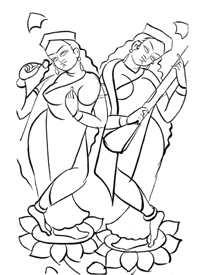

The subjects of Kalighat painting predominantly reflect the orthodox sentiments of painters who feared that social changes would lead to chaos. Husbands beating or killing unfaithful wives, pampered wives riding on the shoulders of henpecked husbands, baboos embracing concubines, good-for-nothing-dandies, cats bearing Hindu holy marks on the forehead as allusion to debauchery, were popular themes. Also popular was the image of Shyamakanta fighting a tiger; an allegory of fighting the British. Another popular image was the Rani of Jhansi riding on horse-back. For religious themes they drew on folklore. In the religious paintings, the same jewellery adorns human and divine beings. The tubular anatomy, arbitrary shading along the contours, heavily simplified forms and rearrangement of the planes, with figures dominating the entire pictorial space without any secondary adornment or props, anticipated quite a few new experiments in modern art.

William Archer in Kalighat Painting informs us that the Paris-based moderns of the early twentieth century vied with each other in acquiring Kalighat Paintings.

One can at random recall Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger and Henri Matisse against the Golap Sundari or the ‘Rose Beauty’ works of Kalighat. The motive in Kalighat was to create a vital pattern that would intuitively apprehend the subject rather than simply represent it. The treatment of planes forged the two-dimensional quality of the pictorial space. The bold lines, the broad planes, the vibrant palette, the linear tensions, and the rhythmic curves are all attuned to a kind of visual music. Unfortunately, the painters left their work unsigned and are lost into oblivion.

Kalighat painting represents the Chaukosh pat or the vertical square formats painting. The standard size was 11 × 17 or 28 × 43 cm. cheap quality paper and cheap ready-made pigments were used. Brushes were made from squirrel and calf hair. The pigments were applied in transparent tones in contrast to traditional Indian tempera or opaque colours.

The brushwork was of four types. One, the tip of a thick brush loaded with water was dipped into black ink or colour to achieve shaded contours, plastic feeling, and tubular mass in a single sweeping stroke. Two, brisk, thin short strokes in black or in a dark colour were used to demarcate figures and the eyes, noses, and fingers, or to denote folds and partings in drapery.

Third, thick black lines were used to outline the pad or the border of the cloth. Hair too was shown as a black block. Fourth, a flat middle tone was used as a colour-wash for clothes to differentiate them from the body. Sometimes, another colour-wash was applied on the figure area. With shaded contours and articulated gesture and movement, the figures attained a plaque-like effect on a neutral unpainted ground. The style is epitomised by formal and linear economy, expressive gestures, and quality brushwork and unerring rhythmic strokes. During the later phase, silver was used for jewellery.

The change in taste brought about by the visually more alluring naturalistic oleographs produced by students of colonial art schools and prints shipped from Germany compelled Kalighat painters to finally withdraw from the market during the early part of the twentieth century. Incidentally, Kalighat painting was the first artistic expression of a subaltern culture in the Indian sub-continent that addressed the consumer directly; it was neither directed by nor produced for the capital or for the ruling authority. [Sovon Som]