Calcutta

Calcutta (Kolkata) a mega city of the world, served as the capital of British Indian Empire till December 1911. Subsequently, it was the capital of the undivided Bengal province. For its elegant colonial architecture, Calcutta was also called the 'City of Palaces'. Located on the left (eastern) bank of the River hughli (Bhagirathi), about 138 kms north of the Bay of Bengal, it is surrounded on the other three sides by the undivided district of Twenty-four Parganas.

Archaeology few recorded instances of chance discovery include: Gupta gold-coin hoard (Kalighat: 1783); potsherds and boar-tusks (Fort William: 1880); black-stone plaques bearing tortoise figures of c. 14th-16th century (Dhapa: 1882); fossils and sculptures (Howrah Bridge construction: 1940s); portion of a Vishnu icon (Behala: 1975). A red sandstone Buddha, resembling that kept in varendra research museum (at Biharail, Rajshahi), and a basalt Vishnu could be located in Chetla. Tusk of Elephas noadicus, an elephant species extingushed about five thousand years back, has been unearthed in Barisha. Erect sundri (Heritiera minor) trunks and several peat layers, discovered frequently during various excavations; provide testimony in favour of multiple geological subsidences in this deltaic zone. Analysing a peat layer located 11.1 to 12.6 metres beneath the land surface of Elgin Road-Chowringhee Road junction; palaeobotanists have discovered fossilised pollen of cultivable grass (probably paddy) ascribable to c 5000 BC. Their radiocarbon investigations have revealed anthropogenic neolithic material of about 2.5 thousand years. These findings convincingly refute the popular belief that the coastal portion of the Gangetic delta, to which Calcutta belongs, is of a recent (c Seventh century AD) formation.

Foundation and early growth The city of Calcutta originates from the east india company's trade settlement right that job charnock obtained for the company from the Mughal government in 1690 in and around the villages of Kalikata, Sutanuti and Govindapur. Sutanuti was then a major thread and textile mart in the region. During his time, Charnock, however, could achieve nothing, except for the construction of a few thatched buildings, before his demise in 1693. Francis Ellis succeeded him as governor of the settlement. Charles Eyre followed Ellis. As the rebellion of shobha singh broke out, the European trading communities sought protection from Nawab ibrahim khan, who granted permission to 'defend them'. Through the payment of Rs 16,000 to Prince farrukh siyar, the company procured a permission from his father Governor azim-us-shan to purchase the renting right of the three villages: Sutanuti, Gobindapur, Kalikata. On 10 November 1698 the British company became the new zamindar of the three hamlets against a petty payment of Rs 1,300 to the original holders, the family of Savarna Chaudhuri.

The Fort William and early stage of urbanisation The construction of the fort though began earlier was not completed until 1707. A wharf was added to the fort in 1710. In the mean time, on 20 August 1700, it was named 'fort william' after William III, the then reigning king of England. While the bachelor clerks (writers) stayed in the quarters within the fort, married officials chose to reside with their families in personal dwellings. As a result, private European houses started cropping up around the fort. Acquisition of the zamindari by the company, opened up employment prospects for the natives as well. They flocked to this nascent habitat adding density to the sparse population. Thus, the process of urbanisation started blossoming on the grounds of the three villages. To satisfy the land hunger of the company and its dependents, the English obtained the emperor's permission to buy another thirty-eight villages from the zamindars in 1717. Of these, five were on the other side of the river (in Howrah), while the rest were contiguous to the three mother villages.

During the maratha raids (Bargi), a general exodus from the western side of the Hughli River led the fugitives to settle in this British territory. The presence of the newly built fort generated a sense of security, which attracted such settlers, enhancing the process of rapid urbanisation. This confidence and the consequent charm were, however, shattered in 1756 when sirajuddaula ousted the English from Calcutta and renamed the city 'Alinagar' after his grandfather alivardi khan. The original name was not restored till January 1758. The British victory at palashi led to the transformation of Calcutta from a mere commercial headquarters of the East India Company. Since then the natives, armenians and other peoples from India and beyond began to settle in the city either for jobs and services or for trade and commerce. New houses were constructed to accommodate the rising population. The settlement of people was following the lines of religion, caste, ethnicity and nationalities. Thus every part of the city was spatially characterised by these marks.

After the American War, free merchants and mariners started flocking to Bengal and agency houses became 'characteristic units of private British trade with the East'. By 1790, fifteen agency houses had developed and the names of William Fairlie, John Fergusson, and John Palmer became famous. Initially these houses carried out purchases and sales for others on a commission basis. But utilising the favorable Act of 1793, the expanding indigo business and the growing foreign trade, they embarked upon independent enterprises acting as bankers, bill-brokers, insurance agents, purveyors, freighters and shipowners. Alexander & Co. started bank of Hindostan, perhaps the first European bank in India, in the 1770s.

The agency houses started shipbuilding industry in the 1780s. Col. Henry Watson (1737-1786), Chief Engineer to the Company, established Bengal's first dockyard in Khidirpur. Import of salt from the Coromandal coast and export of rice, cotton piece goods etc to England provided impetus to shipbuilding. Though most of the ships belonged to European agency houses, Sheikh Gulam Hossain, Dorabjee Byramjee and Ramdulal Dey were among the few Indian exceptions. The risk associated with shipping aroused the need for insurance. From 6 in 1804, there were 15 insurance companies in 1832, working in conjunction with agency houses.

Although the establishment of the British colonial power displaced the former Muslim aristocracy from their ruling status, a new class of rising Muslims gradually crystallised within the Calcutta society. By 1856, there were at least 28 thoroughfares named after them. Sadaruddin - Dedar Buksh - Alimullah Munshi, Imdad Ali - Golam Sobhan Moulvi, Lal-Budhu-Gulu-Nawabdi Ostagar, Karim Buksh Khansama, Rafique Serang, Anis Barber, Nazir Nazibullah, Sharif Daftari, Imam Buksh Thanadar, Khairu Methar had all lent their names to streets despite their varied social positions.

There is, however, indirect evidence of their financial solvency. Even being a scavenger and a tailor respectively, Khairu and Gulu erected imposing mosques. Unfortunately the linguistic identity of these stalwarts is not forthcoming. The surname indicates that Noor Muhammad Sarkar and Sooker Sarkar, after whom two lanes were named, were Bengalis.

Apart from the professions indicated in the above epithets, the general Muslim community included hakims and physicians, moulvis and munshis practising in Sadar Dewani Adalat as vakils, mukhtars and translators, traders dealing in horses, hides, buffalo-horns, 'Mirzapore carpets', cloth and silk piece-goods, glass and earthenware, building materials, lights, opium, indigo, confections etc. The Muslim working class consisted of diamond-cutters, 'gold and silver lace' (zari) makers, printer of Arabic-Persian-Urdu books, engravers, hair-chain and wig makers, coach and palanquin builders, electroplaters and gilders, stable-keepers, butchers etc. So in 1856, only a single year before the sepoy revolt, which vented the venom of the declining Muslim aristocrats, Calcutta was experiencing the rise of another class of Muslims, most of whom were devoid of any glorious familial background. The phenomenon was inherently similar to that of Calcutta's shooting Hindu community, whose upstart character was scathingly criticised by Kaliprasanna Singha in Hutum Pyanchar Naksha (1861-62).

Calcutta's native 'regal' stratum consisted of Raja Rajballabh (Bagbazar; son of Rai Durlabh), Raja Ramlochan (Pathuriaghata; son of Ramcharan Roy, diwan of vansittart), Raja Joynarayan (Bhukailas-Khidirpur; nephew of Gokul Ghoshal, dewan of Verelst), Raja Loknath (Jorasanko; son of Krishnakanta Nandy, Dewan of hastings), and the Jorasanko-Paikpara Raj-family (descendants of Gangagovinda Singha, dewan to the Company). But the most prominent representative of the royal community was Maharaja Nabakrishna of Shobhabazar, the Persian writer of clive, who was awarded the perpetual talukdari of Sutanuti by Hastings in 1778. The Muslim members of this class were the Chitpur nawabs (descendants of reza khan), the Tollygunge Princes (descendants of Tipoo Sultan) and the family of Wazed Ali Shah in Metiabruz.

The officers of these rajas and nawabs as well as those serving the governors, sheriffs, commercial residents, salt agents, courts, pay offices, treasuries, arsenals, customs house, salt committee and various other departments of the Company acquired affluence and conveniently settled in Calcutta. Famous personalities like Nandaram Sen, Churamoni Datta and Tulasiram Ghose accumulated wealth by serving the commercial resident of Dhaka, but chose Calcutta as their permanent abode, the former erecting a lofty temple and the other two spacious dwellings. The surplus resources of this class were invested in purchasing zamindaris all over Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The Tagores of Pathuriaghata and Jorasanko (originally from Jessore) were typical members of this newborn landed aristocratic rank.

Other than the foreign communities and the local natives, Indians from the rest of the subcontinent were also drawn by the irresistible mercantile promise provided by Calcutta. Khatris from Delhi, Benaras, Allahabad, Mathura, Brindaban, Kanauj, Hathras and Mirzapur migrated in the 19th century and prospered through banking, brokery, agency business and trading in grains, seeds, tobacco, perfumery, joss-sticks, cloth, jute, bullion, silver etc. The Jath immigrants dealt predominantly in jewellery, jute and silk. Following the decadence of Surat as a business centre, merchants of various communities from western India (Hindus: Wania and Shravak; Muslims: Shia and Dawoodee Bohra; Parsis) migrated to Calcutta. Match merchant Meherbanji Nanabhai Mehta, Ayub brothers dealing in nuts and rice, tea-magnate MM Ispahani came from Baroda, Kathiawad and Surat respectively. Similarly the Sabarwals, Jethmull-Bhojraj and others from Punjab succeeded in various enterprises. But all their successes were superceded by the pervading prowess of the marwaris. The Barabazar virtually metamorphosed under their influence in the 19th century. While there were 80 Marwaris in Calcutta in 1813, their number rose to 600 in 1833. Censuses depict their steady rise from 1891 to 1911 with a subsequent levelling.

A city creates job opportunities for artisans and labourers as well. Of their various sorts, the braziers of the two Kansariparas (Simla and Bhabanipur) achieved affluence. By virtue of their artistic productions, the potters of Kumortuli moved from obscurity to prominence and the dom or bamboo-cane workers of Rambagan found partial emancipation from abject poverty. Marginal populations like scavengers (hari and dhangar), Bihari milkmen (ahir), Bengali milkmen (goala), blanket weavers (kambulia), butchers (kasai), herb procurers (kaora), jaggery manufacturers (guri), carpenters (chhutar), fishermen (jele), Muslim weavers (jola), Muslim coaldust-cake makers (tikia), cremators (dom), drummers (dhuli), book binders (daftari), washermen (dhoba), Muslim fish-cutters (nikari), painters (patua), vegetable sellers (faria), bullock transporters (baladia), nomads (bedia), jugglers (bhalukwala and dugdugiwala), boatmen (malla), cobblers (muchi), conch designers (shankhari), hunting tribes (shikari), have found recognition in place-names of Calcutta, though their details are not forthcoming today. The prostitutes also formed a distinct palpable group. The concubines of the European and native opulents remained dispersed all over the city in the accommodations provided by their sponsoring consorts, while the public sex-workers remained principally congregated in red-light areas of Sonagachi, Bowbazar, Khidirpur, Kalighat etc.

A final variant unfolded within Calcutta's ethnic diversity through the proselytising pursuits of the European missionaries. A native Christian community developed as a result of their evangelistic efforts. The first major missionary in Calcutta, John Zachariah Kiernander (1711-1799), founded the Old or Mission Church, where' michael madhusudan dutt was later (09.02.1843) baptised. Some of the other pioneer missionaries were Nathaniel Forsyth (London Missionary Society), William Carey (Baptist Missionary Society; later shifted to Srirampur, Hooghly), James Long (Church Missionary Society), Alexander Duff (Church of Scotland) all of them representing the Protestant faith. Their collective contribution to the spread of western education deserves reverence. The Baptists' efforts, in establishing a large press (1818) and Long's empathetic participation in the indigo movement are additionally memorable.

The Jesuits, representing the Catholic sect, arrived in 1834 and founded the St. Xavier's College in 1835. The converts were mainly fetched from the socially backward and economically unfortunate sections of the Bengali society, but Duff succeeded in attracting adherents from the higher classes and castes. Hindu converts like Rev. Krishnamohan Banerjee, Rev. Kalicharan Banerjee, Rev. Lalbihari Dey, Jnanendramohan Tagore (first Bengali barrister), Manohar Ghosh (editor, Shrihatta Prakash) gained prominence. The Christian branch of the Rambagan Datta family, represented by poetess Taru, poets Hurchunder, Girish Chunder and others, was acclaimed for literary achievements. Among the Muslim converts perusing literary activities, Gulzar Shah translated a scripture textbook and Samuel Peer Buksh wrote a play (Bidhaba Biraha, 1860).

The Calcutta police always suffered from deficiency of manpower and in 1778 a rectification was attempted by appointing 700 paiks, 31 thanadars and 34 naibs. On 9 June 1785 the town was divided into 31 divisions, one under each thanadar. However, the department was continually criticised and cornwallis (1793), wellesley (1800), minto (1808), bentinck (1829) tried investigations and redresses to alleviate the disrepute. But almost all bureaucrats censured the entire system before the Fever Hospital Committee. Subsequently JH Patton, the chief magistrate, adopted radical reforms. That his efforts did not bear permanent advantages can be surmised from the fact that Canning had to resort to fresh measures (1860-1862). In the mean time, John Palmer, the 'Prince of Merchants', died a pauper in 1835 and his palatial building-complex in Lalbazar was bought for 2 lakh sicca rupees to provide a permanent headquarter to the Calcutta Police. In 1793 all the darogas, barring a single exception, were Muslims. In May 1850, the tradition was maintained by appointing Sheikh Molaim the first Indian police inspector of Calcutta. The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century saw ruthless police oppression directed against the freedom fighters. Charles Augustus Tegart, Purnachandra Lahiri, Basanta Kumar Chatterjee were notoriously instrumental in protecting the imperial dominance from their emancipator upheaval.

With a swarming population, a comprehensive municipal administration became essential. The Mayor’s Court, constituted under a royal charter of 1727 with a mayor and nine aldermen, imparted civil, criminal and ecclesiastical justice to British inhabitants and levied taxes. In 1794, Justices of Peace were appointed to rectify the defects of the prevailing system. Lack of resources rendered them helpless and in 1803 Wellesley was compelled to adopt reformatory measures. In spite of the subsequent fruitful attempts of the Improvement Committee and the Lottery Committee, the deplorable hygiene of the city urged Lord Auckland to appoint the Fever Hospital and Municipal Improvements Committee in 1836. After colossal pursuits, the committee suggested radical steps. New acts were formulated to appoint commissioners, both elected and selected, to implement the changes and a Town Council, governing finance, roadways, conservancy and water supply, was formed in 1877. Amending acts went on and a final shape was given to the Municipal Corporation through the Act of 1923.

Following the enactment of the Calcutta Electric Lighting Act (1895) and the introduction of the Calcutta Electric Lighting License (1896), the Indian Electric Co. Ltd. became the first licensee (Dec. 1896). The Company soon changed its name to the Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation Ltd. (Feb. 1897) & a generating station was erected in Imambagh Lane with 'Crompton' dynamos, 'Willans' engines and 'Bacock & Wilcox' boilers. The current-supply commenced on and from 17 April 1899.

Thoroughfares are virtually arteries of a city through which surface transport flows. The first spacious highway to be brick-lined was Circular Road (1799; Stone-chip metalling was introduced in Calcutta streets in 1934-35). Since horse-driven carriages need paved roads for plying, they were subsequently introduced at the beginning of the 19th century. Till then, bullock-carts and palanquins were the only modes of local transport. Hindusthanis initially carried by Bengali dulias and bagdis, and palanquins then. But Oriya bearers gradually swept all of them off. Although horse carriages went on increasing in number, variety and grandeur, the parallel prowess of the palanquins persisted until the introduction of automobiles and tramways.

Trams were introduced (24.02.1873) by the Government to create a communication between the Sealdah and Howrah railway stations. The first line ran through Bowbazar Street and Dalhousie Square to the Armenian Ghat on Strand Road, where passengers could avail steamers for crossing the river and reaching Howrah. Due to the loss involved, the service was soon disrupted (20.11.1873) and the railway and vehicles were sold out. A proposal of revival was mooted in 1878 and the previous purchasers formed the Calcutta Tramways Co. After the signing of a contract with the Municipal Corporation, trams were re-introduced (01.11.1880). The western horses pulling the trams often succumbed to the tropical heat and their frequent mortality encouraged experiments with steam engines (1882-83). Later, a proposal from Kilburn & Co. (1896) suggesting the use of electric power for trams was deemed a practical solution and horses were replaced with electricity in 1902. Like, the trams, the earliest buses running between Calcutta and Barrackpore (1830) were driven by horses. Motorbuses were introduced in Calcutta in 1822. Walford & Co. overtook other investors through their introduction of large red buses. They also brought in double-deckers (1926). Abdus Sobhan founded the suburban bus-service. Among private vehicles, bicycles came to Calcutta in 1899 and motorcars in 1896. The business of cabs started in 1906. The Chinese imported rickshaws around 1900, but by 1920 the business was entirely transferred to Indian hands.

A New Era started in Kolkata with the introduction of the railway communications. The idea of connecting Calcutta to the other parts of the sub-continent by railways started with the proposal of the Calcutta-Ranigunge coalfields route (1850). The construction commenced in 1851 and Hooghly (Sept. 1854), Barddhaman (Dec. 1854) and Ranigunge (Feb. 1855) were promptly connected. Between the opening of the Ranigunge - Asansol (1863) and the Dankuni - Sealdah (1932) lines, a network of criscrossing circuits enhanced Calcutta's rail-communication through the Howrah and Sealdah stations.

The grasslands of Dumdum were used for aeroplane landing from 1922. The construction of the aerodrome and the runway commenced around 1928-29 and 1930 respectively. Regular flights started from 1933.

The communication lines connecting Calcutta were dominated by waterways. Indigenous boats for carrying cargo and passengers used these; India General Steam Navigation Co, Rivers Steam Navigation Co and others launched steamers plying to North India. The Port Commissioners' Ferry Service (1907-1927), connecting the major ghats of Calcutta and Howrah, faced financial failure and the mantle was later carried by the Calcutta Steam Navigation Co Ltd.

Opening of the Suez Canal (1869), completion of railways connecting the hinterlands with the ports (1870) and the gradual inclination from agricultural to industrial economy also escalated the importance of this port. To safeguard the prospects of the promising port, a River Trust was contemplated in 1863, inaugurated in 1866, but crumbled within sixteen months due to lack of independent funds. From its ashes, the Calcutta Port Trust came into existence in October 1870 after prolonged deliberations. The energetic commissioners connected the erstwhile jetties forming a continuous wharf, replaced steam cranes with hydraulics, started night shift and stretched their own railway-line within five years. The doubling of tonnage between 1874 and 1884 aroused the necessity of additional accommodation and the Khidirpur docks were constructed (1885-1892). The erection of another new dock-system in Garden Reach, conceived and proposed in 1913-14, was thwarted by the adverse commercial ambience of World War I. It, however, started functioning from February 1929 and was named King George's Dock. But these expansive endeavours were dampened by the economic depression of the 1930s, competition with the railways and political turmoil. Before the conclusion of the convalescence, the curse of the Second World War prevailed and the Khidirpur docks were actually bombed.

Cultural Life Calcutta was once considered the 'cultural capital of the sub-continent' by virtue of its achievements in the field of learning and artistic pursuits. The first learned Sir Willaim jones established the first learned organisation in South Asia, asiatic society, in 1784. The Calcutta Madrasa, calcutta school-book society, Calcutta School Society, fort william college, calcutta medical college, establishment of many newspapers and periodicals, establishment of hindu college and numerous seminaries, schools and colleges, founding of a number of professional associations, numerous printing presses and finally the establishment of calcutta university endowed with many large affiliated colleges made Calcutta culturally a unique city in South Asia in the nineteenth century.

The chariot of modern learning is fuelled by the printing press. The first printer of Calcutta was James Augustus Hicky (1739?-1802), the father of Bengal Gazette or Calcutta General Advertiser. The first Indian printer was Baburam (Khidirpur), a north-Indian Brahmin, while the first Bengali printer cum publisher-journalist-bookseller was Gangakishore Bhattacharya (d. 1831?), the father of Bangal Gejeti. Soon after the establishment of the hindu college (1817) at the present site of the Oriental Seminary, the first press of Battala was established in its close vicinity by Biswanath Deb (c 1818). Till the mid-1870s, Battala was the centre of Bengali printing and publishing. But following the transfer of the Hindu College and the growth of Sanskrit College, Medical College, Hare School & the Calcutta University in Pataldanga, the pivot spontaneously shifted to College Street. With the humble figures of 2 and 7 in 1874 and 1886 respectively, the street could boast of 36 bookshops in 1899. Apart from textbooks, the early publications of Battala and College Street largely concentrated on theology, fictions and erotica. Along with Persian journals like Rammohun Ray's Mirat-ul-Akhwar (1822), Hindi journal Udant Martand (1826), Calcutta saw a flurry of Bengali periodicals like Samachar Chandrika, Sambad Koumudi, Sambad Timirnashak and c. in the 19th century.

Calcutta excelled also in fine arts. 'Brush Club' at calcutta town hall arranged the first art exhibition in 1831. After the transient and obscure existence of the 'Society for Improvement of Oriental Painting and Sculpture' (1842) founded by 'some educated natives', the 'Society for the Promotion of Industrial Art' (1854) made its glorious appearance. This society engendered the 'School of Industrial Art' (16 Aug. 1854), which later became the 'Government School of Art' (1864). The existence of 'Calcutta Art Society' (1889), established by European officers, and the 'Indian Association for the Promotion of Fine Arts and National Gallery' (1892), founded by Bengali painters, was evanescent. Vangiya Kala Sangsad (1905), supported and sponsored by Rabindranath Tagore, Abanindranath and other celebrities also failed to survive. The most reputed art association of twentieth century Calcutta is the 'Indian Society of Oriental Art' (1907), established by connoisseurs. Followers of the western school founded the 'Indian Academy of Art' (1920) and the 'Society of Fine Arts' (1921), while a radical group organised 'Young Artists' Union' (1931) and 'Art Rebel Centre' (1933). These associations perished after fleeting impacts. The 'Academy of Fine Arts' (1933) exceptionally maintained a successful existence.

A great tradition of Calcutta is its indigenous and European theatres and theatre houses. Traditional yatra performances were extremely popular in Calcutta down to the end of the nineteenth century. Gobinda Adhikari (c 1800-1872) and Noko (Lakshman) Dhopa earned fame with their respective yatra troupes in the 19th century. The advent and growing popularity of the western theatre gradually displaced the indigenous. The first British theatrical endeavour, the 'Play House' (Mission Row, 1755) was razed during the siege of Siraj. Two post-Palashi attempts were the Calcutta Theatre (Lyon's Range, 1775-1808) and Mrs Bristow's Theatre (Chowringhee, 1789). The foundation of Calcutta's 'Bengali Theatre' was not laid by a Bengali, but by a Russian called Gerasim Lebedeff (Ezra St., 1795-96). The later English enterprises included the Wheeler Place (1797), Athaeneum (Circular Road, 1812), Chowringhee and San Souci (Park St., 1839) Theatres. Influenced by the trend, Prasannakumar Tagore established his 'Hindu Theatre' (Narkeldanga, 1831). Many theatre houses that were sponsored mostly by the Kolkatta riches followed these pioneer houses.

The emergence of amateur groups was a natural outcome and the exertions of such a team from Bagbazar led to the foundation of the public theatre (National Theatre, Upper Chitpur Road, 07.12.1872-08.03.1873). The intervention of the second enterprise (Oriental Theatre, Cornwallis St., 1873) was followed by the ambitious attempt of Saratchadra Ghosh (Bengal Theatre, Beadon St., (16.08.1873-10.01.1890), who first appointed prostitutes for female roles. This theatre was renamed 'Royal Bengal Theatre' after a 'royal' approbation (11.01.1890-20.04.1901) and after its untimely closure, the premises was used by several groups: Arora (1901-02), Unique (1903-04), National (1905-11), Great National (1911), Grand National (1911-14) Theatres, Thespian Temple (1915-16) and Presidency Theatre (1917-18).

Great National Theatre (Beadon St.), founded by Bhubanmohan Niyogi with technical assistance from Dharmadas Sur, had a checkered existence (31.12.1873-Oct. 1877). Under adverse circumstances, it was rented out to Girishchandra Ghose, who renamed it, National Theatre, but failed to decelerate the decadence. The hall witnessed frequent changes in ownership before and after it's rechristening as Minerva Theatre (1893). Rasaraj Amritalal Bose purchased star Theatre and others in 1887 (Beadon St., 1883), which was erected by Gurmukh Rai Musaddi, consort of Nati binodini dasi. They were later displaced with the goodwill and the hall was called Emerald (1887-96), City (1896-97), Classic (1897-1907), Kohinoor (1907-12), Manomohan (1915-24) Theatres, Natyamandir (of Sisirkumar Bhaduri, 1924-25), Mitra (1926-27) and Art (1928-31) Theatres, before its demolition for the construction of Central Avenue. After being displaced from their previous occupancy, the four partners of Star Theatre migrated to Cornwallis St. This 'Star Theatre' was leased out from 1911 and was used by stalwarts like Amarendranath Datta, Apareshchandra Mukherjee and Sisirkumar Bhaduri during various phases. Playwright Rajkrishna Roy failed to sustain his Bina Theatre (Machuabazar St., 1887-88) and the premises was subsequently occupied by Arya Natyasamaj and Upendranath Das's New National Theatre. Rajkrishna's futile attempt of revival resulted in his bankruptcy (1889). Indian and City Theatres, Victoria Opera House and Gaity Theatre were later users of the hall.

A hall called Curzon Theatre (Harrison Road) was occupied by troupes like City (1900), Grand (1905) and New Classic (1906) Theatres, before its conversion to JF Madan's Alfred Theatre. Even later, it was utilised by Madan's Bengali Theatrical Co. (1923), Sisirkumar Bhaduri (1924), Minerva (due to the blazing of its own hall, 1924), Mitra (1926) Theatres and Natya Bharati (1939-42). Prabodhchandra Guha's Natyaniketan (1931) later became Sisirkumar's Srirangam (1942-1956) and other minor theatres like Cornwallis Theatre (1921), Rangmahal (1931), Cheap Theatre (1933), Rangamahal (1933), Kalika Theatre (1944) also exerted certain influences.

The introduction of the ‘bioscope’ in the early 20th century added a new dimension to the cultural tradition of Calcutta. Jamshedji Framji Madan (1857-1923) through his Elphinstone Bioscope Co. and five cinema-halls in the city achieved the zenith of its commercial prosperity. Inspired by Madan’s initiative, Anadi Basu launched the Aurora Cinema Co (1911) and Aurora Film Corporation (1929). With some renegades from Madan’s team, Dhirendranath Ganguly (popularly called ‘DG’) founded the Indo-British film Co, reaping mixed results. He later joined hands with Pramatheshchandra Barua to set up the British Dominion Films Ltd. But Birendranath Sarkar through his New Theatres Ltd enjoyed the longest command (1931-54) over the Calcutta film-industry. The studios clustering in Tollygunge, this cine-milieu came to be called ‘Tollywood’.

Rammohun Roy introduced Devotional songs, gained impetus from the energy of his adherents. Born in a Brahmo family, Rabindranath was greatly influenced by this Brahma Sangit. The ethos of stage songs, another distinct type maturing through the experiments of Girish Ghose, Amritalal, Kshirodeprasad and Dwijendralal, was also assimilated and transformed by Tagore. His golden touch enriched the Calcutta-born Swadexi compositions as well.

Of the various western sports, cricket was introduced and the Calcutta Cricket Club was founded in the 18th century and India's first organised match took place in this city (18-19 Jan 1804). The glorious emergence of the second largest ground in the world, the Eden Gardens, in the mid-19th century and the establishment of the Ballygange Cricket Club (1864) preceded the visit of the first English team (1888-89). Cricket was popularised among the Bengalis through the ardent exertions of Saradaranjan Ray (1858-1925, from Masua, Kishoreganj) and local clubs like the Sporting Union and the Aryans gathered fame. Calcutta can also be proud of the introduction of hockey (1885), the first Beighton Cup tournament (1895), the foundation of the Bengal Hockey Association (1905) and holding the first national championships (1928).

Calcuttan's citizens have historically evinced interest in horse-racing (Bengal Jockey Club: 1803; Calcutta Turf Club: 1847, renamed Royal Calcutta Turf Club: 1911), golf (the Royal Calcutta Golf Club: 1829), wrestling (introduced by Ambikacharan Guha: 1857), polo (Calcutta Polo Club: 1863; Indian Polo Association: 1892), rugby (1872-76; re-introduced in 1884), boxing (introduced around 1884), lawn tennis (championships started from 1887), billiards (Billiards Association: 1926), basketball (Bengal Basketball Association: 1927), weightlifting (Bengal State Association for Weightlifting: 1933), badminton (All India Badminton Association: 1934), table-tennis (Bengal Table-Tennis Association: 1934), swimming (in various clubs centred around different tanks and pools). However their passion for football remains unparalleled. Englishmen introduced soccer in Calcutta. The first recorded match took place in April 1858 and the Calcutta Football Club was established in 1872. The credit of carrying the ball to the native quarter goes to Nagendraprasad Sarvadhikari, the founder of Wellington (1884), Town (1885) and Shobhabazar (1885) clubs. In 1892, Shobhabazar was the first Indian club to defeat a European team, the East Surrey Regiment, in the Trades Cup. The Indian Football Association (1893) introduced a shield, which became India's most coveted trophy. An emotional outburst occurred when Mohunbagan Athletic Club (1889) won it by defeating East Yorkshire (29.07.1911). The Mohammedan Sporting Club (1891) made its existence gloriously felt by continually winning the IFA League from 1934 to 1941 excepting 1939. In that golden jubilee year of Mohunbagan, all the other three major clubs (Mohammedan, East Bengal and Kalighat) had mutually withdrawn to allow the 'baganis' a victorious celebration. The East Bengal Club (1921) first won the league in 1942 and both the league and the shield in 1945.

Calcutta's cultural significance is not only due to its elitist endeavours. The contributions of its folk specialities are in no way insignificant. The pottery-icon-images of Kumortuli, the bamboo & cane craft of Rambagan, the Kalighat pats, the sandesh of Shimla; the festive mood associated with Durgapuja-Halkhata or Christmas and the New Year's Day; the colourful processions of the Jains (Parsvanath) and Muslims (Muharram); and above all, the boiling adda confer an unique lively distinction to this metropolis.

Architecture The architectural assets of this 'city of palaces' are both domestic and public. The personal residences of British administrators like Hastings (including the Belvedere, Alipore) were essentially western. The households of the rising class under colonial rule were also embellished with massive pediments, prolonged colonnades, and ornate capitals, stucco-terracotta-cast iron decorations, railings and figures. Some representative examples of this type belonged to: Raja Nabakrishna (Shobhabazar), the Tagores (Jorasanko, Pathuriaghata and Emerald Bower: 56, BT Rd), Raja Rajendra Mallik (Marble Palace: Chorbagan), descendants of Hastings' Diwan Ramlochan Ghose (Pathuriaghata and Jorabagan), Raja Digambar Mitra (Jhamapukur). Marble Palace, Chorbagan, Calcutta: A close scrutiny of the decorative components reveals an undercurrent of pre-British elements, both Indian traditional as well as Mughal. The latter is especially conspicuous in the buildings of the Tollygunge and Matiabruz nawabs. The imposing public buildings include the Governor House, Governor's Estates, Writers' Buildings, General Post Office, Collectorate, Old Mint, Town Hall, High Court, Bankshall Court, and Military Accounts' Office.

Calcutta has a wide variety of religious structures: synagogues, Sikh gurdwaras, Buddhist temples, Parsi fire temples, Brahmo prayer halls, Chinese temples, churches, Jain temples, Hindu temples and Muslim mosques, imambaras, khanqahs , dargahs etc. The latter two are dispersed all over the city. The churches belonging to the Armenian, Portuguese, Scottish, English and native congregations are mostly stippled, except the chapels. The prayer halls contain a wide variety of sculptures, paintings, woodwork and inscriptions.

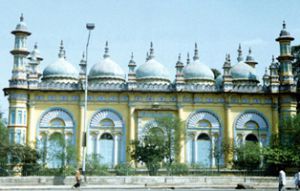

The huge stained glass windows of the St. Paul's Cathedral deserve special mention. Being shrines of a wealthy community, synagogues are equally gorgeous. The Jain temples of Gouriberh and Barabazar are lavish in a different style. The majestic measurements of the Nakhoda Masjid (Sinduriyapati) have led to its fame. But among the Islamic shrines of Calcutta, the dargah of Basiri Shah (Sethpukur Rd, c early 18th century) bears oldest features. The three-domed, double-storied massive mosque of Kitabuddin Sarkar (North Sealdah Rd, 1830) is notable for its spacious prayer halls. The nine-domed huge mosque of Muhammad Ramzan (Nimtala, c 1784) has octagonal minars at the four corners and a praiseworthy mihrab. On the other hand, the mosque of Gulu Ostagar (Darzipara, c early 19th century) has five domes with intervening charchala vaults. Prince Gholam Muhammad, a son of Tipu, erected two impressive mosques at two prominent sites (Tollygunge: 1835; Dharmatala: 1842). But the best contribution of this family is located in their cemetery in Kalighat. This mosque is stylistically uncommon with two domes and a pair of fluted minars.

The ritually significant Kalighat, Chitteswari (Chitpur), Thanthania, Firingi Kali (Bowbazar) temples may be well known, but architectural considerations attach greater emphasis elsewhere. The temple-complexes of Bhukailas (Khidirpur), Tollygunge (Bara and Chhota Rasbari), Paschim Putiari (Karunamoyee), Barisha (of Savarna Choudhuri family); Rameshwar (Nandaram Sen St.), Durgeshwar (Md. Ramzan Lane), Baneshwar (Banamali Sarkar St.), atchala temples; pancharatna temples of Trilokram Pakrashi (Bowbazar), Chandrakumar Roy (Kashipur) and Aghornath Datta (Kalighat); navaratna temples of Mandal Temple Lane, Balaram Ghosh St. and Bethune Row are aesthetically impressive.

Heritage structures also include memorials, of which the private ones are clustered in cemeteries and cremation grounds while the public memorials are widely scattered. The former group includes the excellently erected memorials in the Mysore cemetery (of Tipu-family, Kalighat), the Mysore Memorial of Maharaja Sir Chamrajendra Wadiyar (Keoratala burning-ghat), the obelisks of sir william jones and Major General Charles Stewart ('Hindu Stewart') in South Park Street cemetery. The latter class encompasses the Ochterlony Monument, the Panioty Fountain, the Laskar Memorial, and the Cenotaph etc.

Alike any other city with socially conscious citizens, Calcutta witnessed debates over various issues, unrests, conflicts and movements. Rammohun's crusade against the Sati, Vidyasagar's untiring efforts to exterminate polygamy (among Radiya Kulin Brahmins) and introduce widow re-marriage (among 'upper caste' Hindus), radical Brahmo ambitions to reshape social values and cultivate a 'harmony of religions' utilised the city as a platform. But the most rampant movement that Calcutta experienced was the freedom struggle.

Incidents like the Muraripukur Bomb Case (involving Aurobindo-Barindra Ghose and others), the Dalhousie Square Bomb Case (of Dineshchandra Majumdar and Anujacharan Sen), the 'Verandah Battle' (of Binay-Badal-Dinesh) gave a revolutionary identity to this city. Freedom was indeed achieved for the subcontinent in mid-August, 1947, but Bengal was partitioned. Its greater eastern portion (eastern part with Muslim majority) forming the eastern wing of Pakistan (now independent state of Bangladesh) and its western part (and along with it the prosperous city of Calcutta) became West Bengal province in the union of India. Recently the name of the city has been changed to Kolkata. [Debasis Bose]

Bibliography Jogeshchandra Bagal, Kalikatar Sangskriti-Kendra (in Bangla), Calcutta, 1959; Pradip Sinha, Calcutta in Urban History, Calcutta, 1978; Radharaman Mitra, Kalikata-Darpan (in Bangla), Calcutta, 1980; Sukanta Chaudhuri (ed), Calcutta: the Living City (2 Vols), New Delhi, 1990; Debasis Bose (ed), Kalkatar Purakatha (in Bangla), Calcutta, 1990; Prankrishna Datta, Kalikatar Itibrtta O Anyanya Rachana (in Bangla), Calcutta, 1991.