Dhaka Nawab Estate

Dhaka Nawab Estate was the largest zamindari held by any landholder in Eastern Bengal during the colonial period. The founding members of the Dhaka Nawab Estate were Khwaja Hafizullah and his nephew khwaja alimullah. So far as the land acquisition, land management and accumulation of wealth and power are concerned the greatest figures of the estate were Khwaja abdul ghani and his son khwaja ahsanullah. Though they had nothing to do with the Mughal nawabs of Dhaka or Murshidabad, they came to be known as the Dhaka Nawabs from 1875. However, in the first half of the twentieth century, the family had successfully transformed its landholding status into political power. Until early 1950s, the ahsan manzil, the headquarters of the Nawab Estate, was the focal point of Muslim politics in Eastern Bengal.

Rise of the Estate The ancestors of the Khwajas are said to have come originally from Kashmir. As traders of gold dust and skins they first settled in Sylhet in the mid-eighteenth century and later towards the close of the eighteenth century moved to Dhaka in search of better prospects. The earliest founding man of the Dhaka Nawab Estate is Maulvi Hafizullah. In collaboration with the Greek and Armenian merchants in Dhaka, he developed a flourishing business in hides and skins, salt and spices. Under the operation of the permanent settlement zamindari estates of the defaulting proprietors were on sale everywhere in Bengal. Hafizullah decided to buy a few lots for enhancing the security of his newly acquired fortune. The first lot that Maulvi Hafizullah purchased seems to have been a 4-anna share in the Atia pargana in the then Mymensingh district (now in the Tangail district). He acquired it in 1806 on the strength of a mortgage bond for Rs. 40,000.

For Hafizullah, the acquisition of the Atia pargana's 4-anna share proved to be highly profitable. Inspired by its profit and associated prestige, he continued to buy landed property from time to time without, of course, impairing his original business concerns. Hafizullah's greatest lucky buy was Aila Phuljhuri in the sundarbans. In 1812, he bought these mostly uncultivated tracts of lands measuring about 44000 acres only for Rs 21000 at an incredible revenue demand of only Rs 372 a year. Phuljhuri was the place where the first clearing of the Bakarganj Sundarbans was effected, and was rapidly developing agriculturally. During the cess operations conducted in the late 1870s, its estimated total rental income appeared as high as Rs 2,20,502.

On his death, the estate of Khwaja Hafizullah descended on his nephew Khwaja Alimullah (son of his deceased elder brother Ahsanullah) whom he groomed as an astute estate manager. Like Hafizullah, Alimullah was also an enterprising man and he purchased several profitable lots in his own name. His landed acquisitions were added to those of his uncle, Hafizullah. The merger, which was effected due to an absence of any surviving male successor of Hafizullah, consequently made the united zamindari one of the biggest in the province. Before his death (1854), Alimullah made an waqf for a united status of the zamindari which was to be managed jointly by a mutwalli.

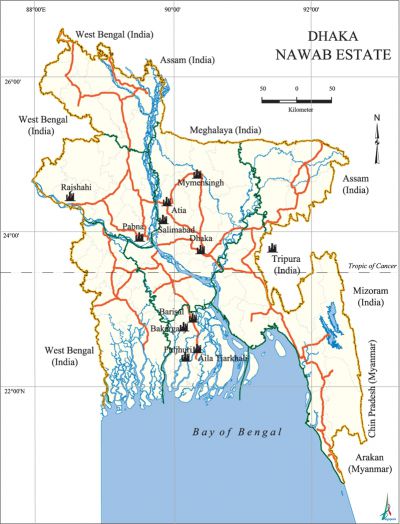

It was on the succession of Khwaja Abdul Ghani Mia (son of Alimullah) to the management that the prosperity of the house reached its zenith. Under Ghani Mia's management the estate was further expanded territorially. Under him the land control of the family was extended to many parganas in the districts of Dhaka, Bakarganj, Tripura, and Mymensingh. For management he split the zamindari into 26 sub-circles of which 11 were in Bakarganj, 4 in Tripura, 4 in West Mymensingh and Pabna, 3 in East Mymensingh and Sylhet and 4 in Dhaka. Each circle had a kachhari headed by a naib with a number of amla (officials). The Ahsan Manzil made the top of the pyramidal structure of zamindari management. The estate paid Rs 3,20,964 in government revenue and earned in rental income after all deductions Rs 5,80,857 in 1904.

With Ghani Mia the Khwaja family for the first time developed interest in the politics and social works of the country. His acts of public and private charity were very numerous and impressive. In aid of schools and colleges, hospitals and dispensaries, clubs and societies, mosques and tombs, the sick and the poor, Ghani spent very large sums. It was he who introduced running water and gaslight in Dhaka at his own expense. Governor General Lord Northbrook laid the foundation stone of Ghani Mia's Water Works on 6 August 1874. Organising the Dhaka people into panchayet mahallas was a great mark of leadership and social commitment on the part of Ghani Mia.

His support to the British raj at the time of the sepoy revolt, 1857 and continued loyalty since then enhanced his image in the estimation of the colonial regime. In organising the non-formal government called panchayet system in Dhaka, Ghani Mia received official support. He was made a nominated commissioner when the Dhaka Municipality was established in 1864. In appreciation of his leadership and benevolence he was made an Honorary Magistrate, a member of the Bengal Legislative Council in 1866, an additional Member of the Governor General's Legislative Council in 1867 and was created a CSI in 1871. He was vested with the personal title of 'Nawab' in 1875, which was made hereditary in 1877. Nawab Abdul Ghani was decorated with KCSI in 1886. He died in 1896, highly esteemed by all classes, as the wealthiest and most influential person in Eastern Bengal and the patriarch of Dhaka city.

Long before his death, Ghani installed his capable son, Nawab Khwaja Ahsanullah on the gadi. Nawab Sir Khwaja Ahsanullah upheld worthily all the praiseworthy traditions set up by Alimullah and Abdul Ghani. Under his management, the zamindari neither increased nor decreased. Instead of going for an expansion, Ahsanullah rather adopted the strategy to consolidate the zamindari control that was threatened by the operation of the bengal tenancy act, 1885. After the enactment of this Act, farsighted zamindars showed tendency of buying intermediate tenures and raiyati rights. Such an effort was made in order to preserve the classical control over the tenants under the changed circumstances. Ahsanullah used the family surplus in buying numerous tenurial and raiyati rights and settled them as khas. Under this arrangements the Khwajas became their own tenants. This farsighted act had eventually saved the estate from colossal loss when the zamindari system was abolished in 1951.

However, Ahsanullah was a strong supporter of the British raj and the raj also in turn supported him strongly in various forms. For many years he was a Municipal Commissioner though he seldom cared to attend the meetings of the Municipality. He had his own private system of city management that had been arguably operating far more efficiently than that of the Municipality. He was made a Nawab in 1875, CIE in 1891, a Nawab Bahadur in 1892, KCIE in 1897 and a Member of the Governor General's Legislative Council once in 1890 and again in 1899. Nawab Ahsanullah died on 16 December 1901. His death was condoled by the Governor General and Lieutenant Governor and all the outstanding personalities of Bengal.

If the nineteenth century is the period of rise and fulfillment of the Dhaka Nawab family socially and politically, the twentieth century had witnessed its gradual decline and virtual end. Nawab Salimullah, the eldest son of Ahsanullah took up the management of the zamindari in 1902. But soon family feuds started and Salimullah lost the grip on the estate. The estate management deteriorated to the extent of rising revenue arrears and estate debts. For political considerations, the government backed up Nawab Salimullah financially. The government support included a confidential official loan to Salimullah (1912) to clear up his personal debts to the Hindu mahajans.

Preserving the loyalist landed families of the country was a policy of the colonial regime.The backdrop of such a policy was the increasing pressure exerted on the government by the nationalist elements. With this end in view the tottering Dhaka Nawab Estate was brought under the Court of Wards in September 1907. The first steward of the Estate was HCF Meyer who was followed by LG Pillen, PJ Griffith, and PD Martin, all members of the Indian civil service. The Dhaka Nawab Estate was abolished in 1952 under the east bengal estate acquisition and tenancy act, 1950. Only the Ahsan Manzil complex and khas lands held under raiyati rights were exempted from the operation of the Acquisition Act. But due to many unresolved family claims many assets of the Estate were still controlled by the Court of Wards. The land reforms board, the successor of the erstwhile Court of Wards, is still holding those assets on behalf of the family. [M Ali Akbar]