Mahasthan

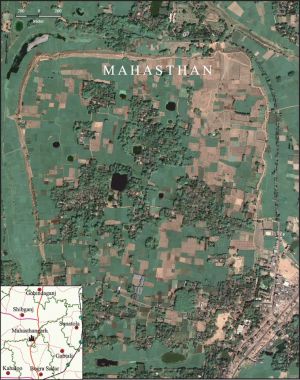

Mahasthan or Mahasthangarh represents the earliest and the largest archaeological site in Bangladesh, consists of the ruins of the ancient city of pundranagara. The site is 13 km north of Bogra town on the Dhaka-Dinajpur highway. The ruins form an oblong plateau measuring 1500m N-S and 1400m E-W and are enclosed on their four sides by rampart walls that rise to an average height of 6m from river level. The highest point within the enclosure at the southeast corner is occupied by the mazar (tomb) of shah sultan mahisawar and by a mosque of the Mughal Emperor farrukh siyar. The latter has been enclosed by a modern mosque, which has been extended recently, a development that precludes the scope of excavation here in future.

The northern, western and southern sides of the fortified city were encircled by a deep moat, traces of which are visible in the former two sides and partly in the latter side. The river Karatoya flows on the eastern side. The moat and the river might have served as a second line of defence of the fort city. Many isolated mounds occur at various places outside the city within a radius of 8 km on the north, south and west, testifying to the existence of suburbs of the ancient provincial capital.

Many travellers and scholars, notably buchanan, O'Donnell, Westmacott, beveridge and Sir Alexander cunningham visited this site and mentioned it in their reports. But it was Cuningham who identified these ruins as the ancient city of Pundranagara in 1879.

The city was probably founded by the Mauryas, as testified by a fragmentary stone inscription in the Brahmi script (mahasthan brahmi inscription) mentioning Pudanagala (Pundranagara). It was continuously inhabited for a long span of time.

The first regular excavation was conducted at the site in 1928-29 by the Archaeological Survey of India under the guidance of KN Diksit, and was confined to three mounds locally known as bairagir bhita, govinda bhita and a portion of the eastern rampart, together with the bastion known as munir ghun. Work was then suspended for three decades. It was resumed in the early sixties when the northern rampart area, parasuram palace (Parashuramer Prasad), mazar area, khodar pathar bhita, mankalir kunda mound and other places were excavated. The preliminary report of these excavations was published in 1975. After about two decades excavation was once more resumed in 1988.

It then continued for almost every year up to 1991. During this period the work was confined to areas near the mazar and the northern and eastern rampart walls. But the work done in this phase was of negligible scope compared to the vastness of the site. The history and cultural sequence of the site were yet to be established.

The necessity of a thorough investigation for the reconstruction of the early history of the site and the region, and for the understanding of the organisation of the ancient city continued to be felt. Consequently, under an agreement between the governments of Bangladesh and France (1992) a joint venture by Bangladeshi and French archaeologists was undertaken in early 1993. Since then archaeological investigation is being carried out every year in an area close to the middle of the eastern rampart. Excavations have also been conducted earlier by the Department of Archaeology, Bangladesh, in a number of sites outside the fortified city such as bhasu viharA (Bhasu Vihara), bihar dhap, mangalkot and Godaibari.

Excavation at the city has reached virgin soil at several points. Of these, the recent excavations conducted by the France-Bangladesh mission have revealed 18 building levels. The works carried out at different times from 1929 to the present (including France-Bangladesh expeditions) reveal the following cultural sequence:

Period I represents the pre-Mauryan cultural phase characterised by large quantity of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) of phase B, Rouletted ware, Black and Red Ware (BRW), black slipped ware, grey ware, stool querns, mud-built houses (kitchen) with mud floors, hearths and post-holes. Fine NBPW are more numerous in the lowermost levels; dishes, cups, beakers and bowls are the predominant types. Only a brick-paved floor has been traced in a very restricted area of this level, but no wall associated with this floor has been exposed till now. It appears that the earliest settlement took place over the Pliestocene formation. No precise date for this early settlement could be ascertained. But some radiocarbon dates from the upper level go back to late 4th century BC. This indicates that the 'early settlement' is of pre-Mauryan period. It needs to be ascertained whether this phase belongs to Nanda or pre/proto-historic culture.

Period II is represented by the occurrence of broken tiles (the earliest evidence so far known of this type of roofing), brick-bats used as temper or binding material in the construction of mud walls (also sometimes reused in a domestic context ie, fire place, terracotta ring well),

NBPW, common wares of pale red or buff colour, ring stone, bronze mirror, bronze lamp, copper cast coins, terracotta plaques, terracotta animal figurines, semi-precious stone beads, stone mullers and querns. A few calibrated radiocarbon dates (366-162 BC, 371-173 BC) and the cultural materials indicate that this phase represents the Mauryan period.

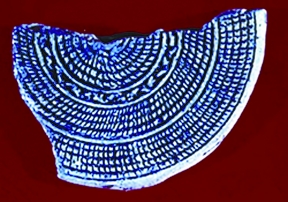

Period III represents the post-Mauryan (Shunga-Kusana) phase. It is marked by substantial architectural remains of large sized and better-preserved brick built houses, brick-paved floors, post-holes, terracotta ring wells, large quantity of terracotta plaques of Shunga affiliation, beads of semi-precious stones (agate, carnelion, quartz), silver punch marked coins, silver bangle, copper cast coins, antimony rods, terracotta pinnacle, large quantity of common pale red or buff wares (especially dishes, cups and bowls) and grey wares. NBPW of course fabric occurs in less frequency compared to Mauryan level. A few radiocarbon dates give calibrated intervals 197-46 BC, 60 BC-172 AD, 40 BC-122 AD.

Period IV represents the Kusana-Gupta phase. It is marked by the discovery of substantial amount of Kusana pottery and terracotta figurines with definite stylistic affiliation of the contemporary idiom. The principal pottery types are handled cooking vessels with incised designs, saucers, bowls, sprinklers and lids. Architectural remains are scanty compared to its lower and upper phases. Building materials are represented by small fragments of bricks. Other cultural materials are terracotta beads, bowls, stone and glass beads, glass bangles, terracotta seals and sealings. Gold coins

Period V represents the Gupta and late-Gupta phase. Radiocarbon data of this phase give calibrated dates between 361 AD and 594 AD. The phase yielded remains of a massive brick structure of a temple called Govinda Bhita, located close to the fort-city, belonging to the late Gupta period, as well as other brick structures - houses, floors, streets - in the city, and huge antiquities, including terracotta plaques of the characteristic style, seals, sealings, beads of terracotta, glass and semi-precious stones, terracotta balls, discs, copper and iron objects, and stamped wares.

Period VI represents the Pala phase, evidenced by architectural remains of several sites scattered throughout the eastern side of the city, like Khodar Pathar Bhita, Mankalir Kunda, Parasuram's Palace and Bairagir Bhita. This was the most flourishing phase and during this period a large number of Buddhist establishments were erected outside the city.

Period VII represents the Muslim phase testified by the architectural remains of a 15 domed mosque superimposed over the earlier period remains at Mankalir Kunda, a single domed mosque built by Farrukh Siyar, and other antiquities like Chinese celadon and glazed ware typical of the age.

Bairagir Bhita, Khodar Pathar Bhita, Mankalir Kunda Mound, Parasuram’s Palace Mound and Jiat Kunda are some sites inside the city which have yielded archaeological objects of interest. In addition to these sites, excavations in 1988-91 have revealed three gateways of the city, a considerable portion of the northern and eastern rampart, and a temple complex near the mazar area. Out of the three gateways, two are in the northern rampart; one is 5m wide and 5.8m long and is located 442m eastward from the northwest corner of the fort, and the other, situated 6.5m eastward, is 1.6m wide. The gateways were in use in two phases related to the early and later Pala periods. The only gateway in the eastern rampart, located almost in its middle and 100m east of Parasuram’s Palace, is about 5m wide and is thought to have been built in the late Pala period over the remains of an earlier gateway, which has not yet been fully exposed.

All the gateway complexes are provided with guardrooms in the inner side, and bastions projecting outside the rampart walls. The temple complex exposed in the mazar area does not reveal a coherent plan. It appears to have been built and rebuilt in five phases, one superimposed over the other, covering the Pala period. The antiquities recovered from the site include a few large size terracotta plaques, toys, balls, ornamental bricks, and earthenwares.

The rampart of the city, built with burnt bricks, belongs to six building periods. The earliest one belonged to the Maurya period, whereas the subsequent ones correspond to Shunga-Kusana, Gupta, early Pala, late Pala, and Sultanate periods. These walls were successively built one above the other.

Thus we get a succession of rampart walls as we see the succession of cultural remains inside the city. However, the correlation between the cultural remains of the city of the earliest level and the earliest rampart wall (mud wall?) remains to be established.

Govinda Bhita, laksindarer medh, Bhasu Vihar, Vihar Dhap, Mangalkot and Godaibadi Dhap are excavated sites located outside the city but within its vicinity. Many more mounds lie scattered in adjacent villages, which are believed to contain cultural remains of the suburbs of the ancient fortified city of Pundranagar. [Shafiqul Alam]

Bibliography KN Dikshit, 'Annual Report 1928-29', Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi, 1933; A Cunningham, 'Report of a Tour in Bihar and Bengal in 1879-1880 From Patna to Sonargaon', Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi 1969; N Ahmed, Mahasthan: A Preliminary Report of The Recent Archaeological Excavations at Mahasthangarh, Dacca, 1975; Shafiqul Alam and J-F Salle (ed), France-Bangladesh Joint Venture Excavations at Mahasthangarh First Interim Report 1993-1999, Dhaka, 2001.