Tea Industry

Tea Industry developed during the nineteenth century in Assam and especially in Sylhet. Primarily, the British planters initiated the cultivation of tea on the slopes of the hillocks of Sylhet and the highlands of Assam. In 1839, Assam Tea Company was formed at a meeting of some British capitalists and Indian entrepreneurs like prince dwarakanath tagore, Babu Motilal Sil, Haji Hashem Ispahani and others. The Company formally launched on 12 February 1839 in London with a capital of A3300,000 ($500,000) was later merged with the Bengal Tea Association of Kolkata.

Robert Bruce first discovered tea plant in Assam in 1834. In 1855, an indigenous tea plant was discovered in Chandkhani hillock of Sylhet. At about the same time, wild tea plant was found along the Khasi and Jaintia hills. Tea cultivation also started in Chittagong in 1840 with few plants imported from China and some plants of China origin developed in the Calcutta Botanical Garden. The first tea garden of Bangladesh was established in 1854 at Malnichhara in Sylhet. Two other tea gardens, Lalchand and Matiranga were established in 1860.

Initially, the tea plantation was the outcome of individual venture. But following the depression and slump of the 1860s the development of new plantation came to a stand still, and the tea industry turned to be a monopoly of the big companies. For example, James Finlay dominated the plantation venture in Sylhet after the depression. However, in the closing years of the nineteenth century, a small group of local entrepreneurs were involved in tea plantation. Eventually, the European planters and companies faced new competitors, but the local planters could not stand in their way because of their dependence on the European planters for technological know-how. There developed an interaction of the Europeans and local entrepreneurs. The partition of India in 1947 and the subsequent dislocation of the Hindu entrepreneurs, paved the way for the dominance of some capitalists of West Pakistan and a group of Urdu speaking north Indian Muslims migrating to Pakistan.

Tea estates in Bangladesh were owned and managed by Bangladeshi Companies, Sterling Companies and Proprietorship Concerns. The term Bangladeshi Companies refers to the companies formed and registered in the country under the Companies Act, 1913 and also under earlier Acts. Sterling Companies are foreign companies, mainly originating in the United Kingdom and multinational in nature. The average size of the tea estate of the Sterling Companies was 1648 acres, and that of Bangladeshi Companies 669 acres, while that of proprietorship concern 343 acres.

At first emphasis was given to the introduction of Chinese seeds. Forty two thousand Chinese plants were reared in the Calcutta Botanical Gardens and distributed in the Himalayas and Assam. Most of them died in transport, and the rest were planted, but did not survive. This proved to be fortunate, because the experts thereafter paid no further attention to China, and the enthusiasts on the spot had to continue their efforts with the indigenous plants. Thus the idea of 'hybrid tea' was abandoned in favour of an indigenous variety. Assam Brand Tea obtained the seal of imperial approbation in 1851. In Sylhet 'wild' or 'indigenous' tea was discovered on 4 January 1856. This discovery created enthusiasm at the local level and particularly the European planters and officials envisaged an extension of the tea frontier with Sylhet. In his report to the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, the Magistrate of Sylhet, TP Larkins mentioned, 'Tea Plants in great abundance are growing in Chandkhanee Hills85I have sent specimens this day to the Agricultural Society of India for analysing. Larkins also suggested that in consequence of the importance of this discovery, the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal might sanction reward of Rupees 50 to the lucky discoverer, Mohammad Warish. Thus an ordinary native was rewarded for his contribution.

The overseas companies in early phase Tea plantation as an investment in Assam and Sylhet appeared quite lucrative in the 1860s, which was known as tea mania because the white people thought that it was a California style 'Gold Rush' in the Indian context. It was believed that anybody could run a tea garden, including retired military officers, medical men, engineers, veterinary surgeons, steamer captains, chemists, shopkeepers of all kinds, even policemen and clerks. As a result of over-enthusiasm, there was a crash in the tea sector in the 1860s. However, this crisis was short-lived and the plantations became firmly established as a commercial venture by the 1870s. In the 1880s, the companies had replaced individual efforts. DH Buchanan suggests that the tea industry had successfully gathered British capital from the United Kingdom, available between 1880 and 1910. But AK Bagchi argues that largest portion of the capital had been extracted from the Indian colony. The moving force behind the expansion of plantations was the sustained flow of capital from London, Kolkata and locally available sources.

Entrepreneur James Finlay founded a company in 1745 at Glasgow. It was under James's second son, Kirkman Finlay that the company expanded its markets in Europe, America and India. In 1816, two young assistants of Finlay set up agency houses in Kolkata and Colombo. In 1861 John Muir became a partner and soon bought the shares. In 1882, John Muir floated two companies, the North Sylhet Tea Company and the South Sylhet Tea Company. Under Muir, the Company was renamed as Finlay and Muir, but was popularly known as James Finlay. Finlay Company was carried on with a capital of A35,500,000. By the 1950s, Finlay had 270,000 acres of land of which about 77,000 acres were planted with tea, giving employment to about 70,000 locals. Besides sending tea to the United Kingdom, it introduced Indian tea to America, Australia, Russia and Europe. Thus, the James Finlay Company contributed significantly in making tea a popular global drink. Taylor Maps of the Tea Districts: Sylhet with Full Index of the Tea Garden published in 1910, provides a clear picture of the domination of European tea companies over the tea estates.

Table 1 Position of European Companies and Agency houses in tea industry.

| Agency house | Acres of land |

| James Finlay | 26,935 |

| Octavius Steel | 14,776 |

| McLeod and Co | 5337 |

| Shaw and Wallace | 4180 |

| Barlow and Co | 3241 |

| Planters Stores and Agencies | 3028 |

| King Hamilton and Co | 2095 |

| Duncan Brothers | 1848 |

| Barry and Co | 1315 |

| Williamson and Magor | 1280 |

| J Mackillican | 1219 |

| MacNeill | 849 |

| Andrew Yule | 799 |

| Grindlay | 616 |

| Kilburn Co | 400 |

| Waker | 327 |

| W Cresswel | 255 |

| National Agency | 237 |

| Total Acres | 68,737 |

James Finlay established dominance through securing grants of wastelands from the government, from the Maharaja of Tripura and by purchasing lands from people. In the early 1880s, John Muir purchased large tracts of wasteland in Balisera, about 13,609 acres from the Maharaja.

Tea production in Sylhet increased with remarkable rapidity. By 1893 the yield amounted to 20,627,000 lbs, which nearly equalled that of Sibsagar, the largest tea-producing district in Assam. The upward tendency was maintained, and in 1900 there were 71,490 acres under cultivation which yielded 35,042,000 lbs of tea. This was more than 4,000,000 lbs in excess of that produced in any other districts of the Province. During the period 1904-1905, out of 123 tea estates in Sylhet, as many as 110 were owned by Europeans. In 1910, European companies owned 95% of tea producing land while local people owned only 5%. However, by the late 1920s, local people owned 10% of tea lands.

Progress of tea industry In the 1870s, machineries for tea industries were imported from Britain. A major difficulty was the fuel supply, and efforts were taken to achieve a breakthrough from 'charcoal'. So gradually coal and oil replaced charcoal. Modernisation of the fuel supply not only increased tea production and improved the quality of tea, but also reduced the destruction of forest. Completion of the assam-bengal railway in the 1890s and the expansion of waterways, also improved the condition of fuel supply. The railway also contributed to the expansion of tea production by reducing freight charges for the tea containers. Knowledge and management skill had created 'supremacy' of overseas planters and they were benefited by local knowledge and cooperation while the indigenous planters were benefited from the process of technology transfer and the exchange of ideas. In the 1930s, an experienced native manager Avinas Dutta wrote a Handbook that dealt with the 'conflicting opinions' of the scientists. He claimed that his book would be a boost to the empirical knowledge for both native and overseas planters. The tilla babus (head of a block in the garden) helped the Europeans to cultivate the tea plants, in soil tests and to understand the weather. Some babus even led the opening of tea gardens for the Europeans such as the New Sylhet Tea Estate initially belonged to a babu. Thus new capitalist venture addressed the role of the native elites.

Indigenous planters and joint stock companies' In the formation of the Assam Tea Company in 1839, there were signs of the involvement of both Hindu and Muslim entrepreneurs. In 1876, they launched the Cachar Native Joint Stock Company. It was the first native concern in tea plantation not only in Assam but also in Bengal. The Cachar Native Joint Stock Company was floated by the Bangalis in the Surma valley (Sylhet). A famous lawyer from Sylhet, Musaraf Ali, along with his Hindu friends formed this Company while Musaraf Ali's personal friend and a senior bureaucrat, Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee, provided official backing. In 1880, Bharat Samity Ltd was formed in Sylhet which owned the Kalinagar Tea Garden. The authorised capital of Bharat Samity was 500,000 rupees, subscribed capital of 177,500 rupees and paid-up capital was 100,475 rupees. The Indeswar Tea and Trading Company Limited registered in 1896 had an authorised capital of 100,000 rupees, subscribed capital of 100,000 rupees and paid-up capital of 88,785 rupees. Financial constraints prevented indigenous planters from extension of cultivation, and the majority of them had no factory of their own; they had to send their green leaves for manufacture to nearby European gardens. Nonetheless, the role of the zaminders in Sylhet appears to be vital as they were granting land to overseas planters as well as opening gardens by themselves. Planter Braja Nath Chowdhury worked closely with an overseas firm and sold his forestland to Duncan Brothers. As a result Braja Nath received some valuable consultation from Mr Machmean of Duncan Brothers who helped him to open a tea garden in the late nineteenth century. Four decades later Braja Nath's grandson Brojendra Narayan Chowdhury opened Mahabir Tea Estate on an area of 1065 acres at Kamalpur in Tripura. It was named after the king of Tripura, Maharaja Birbikram Manikya Bahadur.

In 1911, Khan Bahadur Syed Abdul Majid, the first native Minister of Assam, launched the All India Tea Company with the help of Hindu elites of Sylhet. The authorised capital of the company was 100,0000 rupees, subscribed capital was 847,500 rupees and paid up capital was 710,985 rupees. Achyut Charan Chowdhury mentions that in 1910 the local entrepreneurs owned 10 tea gardens. Nawab Ali Amjad Khan, zamindar of Sylhet, established the Rangirchhara tea garden which was the largest local tea garden. A number of respectable Muslims had also shown modest interest in tea plantation. Mohammad Bakht Majumder, Karim Baksh, Golam Rabbani, Sayed Abdul Majid jointly owned the Brahmanchhara tea estate in 1904. Syed Ali Akbar Khandakar was the owner of the Pallakandi tea estate in Hingajia in South Sylhet. Zamindar Abdur Rashid Chowdhury and his son Aminur Rashid Chowdhury were prominent tea planters in Sylhet whose tea estates still exist as major local venture.

In 1921-22, in the tea sector, there were 29 native joint stock companies in Assam. Out of these companies, 23 were registered in Sylhet, 3 in Cachar and only 3 in Assam. Bangalis in Kolkata, with the help of Sylheti planters and elites, established agency houses. These were trading concerns which involved networking and business management. The following table indicates a picture of the early twentieth century agency business between Sylhet and Kolkata where all were natives.

Table 2 Native agents and owners in 1910.

| Native agents/owners | Tea estate | Gardens |

| Gagon Chandra Pal, Kolkata | Bidyanagar Tea Estate | Bidyanagar, Chandnighat, Ramnagar, Chunatigool and Krishnanagar |

| Dutta and Sons, Kolkata | Dakshingul Tea Estate | Dakshingul, Barlekha |

| NN Chowdhury, Kolkata | Govindapur Tea Estate | Govindapur |

| Gagon Dutta, Kolkata | Kalinagar Tea Estate | Kalinagar, Ratbari |

| Iswar Chandra Dutta and Prasanna Kumar Dutta | Madanpore Tea Estate | Madanpore, Latu |

Sources Compiled from Taylor’s Map, 1910.

Pakistan Period After 1947, the tea industry entered a new phase. Its major part gradually gradually fell into the control of West Pakistani capitalists. The partition resulted in a major dislocation of the Hindu capitalists and consequently most of them left for India. At this juncture the West Pakistani capitalists came forward to seize the opportunity. In this process they could enlist the patronisation and support of the central government. An assessment of 1966 shows that out of the total of 114 tea gardens, West Pakistani capitalists were the owners of 56 tea gardens, while the Europeans possessed 47 gardens, and the Bangali entrepreneurs had the ownership of only 11 tea gardens. The statistics of 1970 reveals that out of a total of 162 tea gardens 74 gardens belonged to West Pakistani entrepreneurs.

Bangladesh period The tea industry sustained major damage during the war of liberation in 1971. The Bangladesh government appointed a committee in 1972 to investigate into the problems faced by the tea planters. Some useful suggestions were: (a) to raise productivity, (b) to reduce cost of production, and (c) to promote and strengthen the process of marketing.

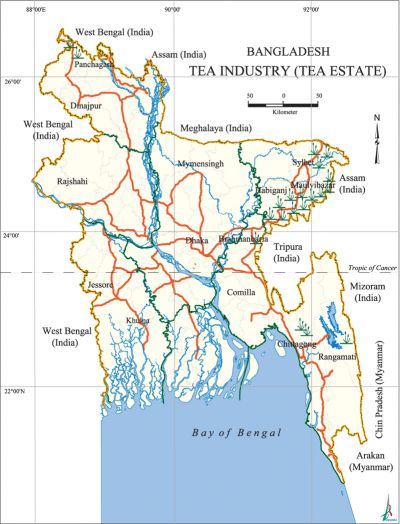

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s overseas firms remained in the dominant position both in area and in production. The gardens owned by foreign sterling companies were generally about three times bigger than the locally owned gardens and the production per acre was higher. In 2010 the number of tea gardens is 162. Of these gardens, 135 are in Sylhet division and 23 are in Chittagong division, and the newly developed 4 gardens belong to Rangpur division. The tea estates in Bangladesh annually produce about 59 million kg of tea. In 2000, country occupied 9th position among the 30 tea producing countries of the world, but in 2008 it downgraded to the 11th position. Production rose by one percent to 59.24 million kg but exports fell 68 percent to 2.53 million kg in 2009. Despite an increase in yields, exports are likely to fall further as the internal consumption is rising. By comparison, Bangladesh tea exports peaked at 31 million kg in 1980 when production was 40 million kg. Bangladesh exports tea to the following countries: Afghanistan, Australia, Belgium, China, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhistan, Kenya, Kuwait, KSA, Kyrghistan, Oman, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, Sudan, Switzerland, Taiwan, UAE, UK and USA.

Before 1947, London worked as the main export centre of tea trade. After partition, the British planters organised auction market in London and the Indians organised their auction market in Kolkata. In the then Pakistan, auction market was set up at Chittagong. Auctioning organisations also offer broker services and other facilities to producers. Brokers advance funds to producers or stand surety to banks for repayment of bank loan. Brokerage houses have rendered tea marketing smooth and economical through tea tasting, cataloging, sampling, evaluating and statistical services. Bankers helped tea exporters with advances against shipping documents.

Employment and labour About 0.15 million people are directly employed in the tea industry. Many more people are indirectly employed in other sectors related to tea processing and business.. In the 1970s, some 120,000 permanent workers both men and women with 350,000 dependants were employed. The present generation of tea garden workers comprises heirs of workforce recruited by the planters from Choto Nagpur and Jharkhand, and other parts of India in the middle of the nineteenth century. These workers have been living in the tea gardens permanently in houses specifically made for them. Tea industry of the country faces problems as some gardens become sick and their workers are 'surplus'. [Ashfaque Hossain]

Bibliography James Finlay Papers, UGD91/8/3/6/2/16; H Cottam, Tea Cultivation in Assam, Colombo, 1877; Harold H Mann, Tea Soils of Cachar and Sylhet, Calcutta, 1903; Avinas Chandra Dutta, Handbook of Tea Manufacture, Habiganj, 1933; Anonymous, James Finlay and Company Limited: manufacturers and East India merchants, 1750-1950, Glasgow, 1951; Proceedings of the Tea Conference held at Sylhet on 26 and 27 January 1949, Ministry of Commerce, Government of Pakistan, 1949; GP Stewart, The Rough and Smooth (autobiography); Bangladeshiyo Cha Sangsad, Annual Report, Srimongal, 1984.

See also tea; bangladesh tea research institute; bangladesh tea board.